Collaborative Safety Plan

Individualized Approach

All individuals identified as at risk of suicide should have a safety plan. Collaborative safety planning is becoming a standard in many behavioral health organizations and health systems.

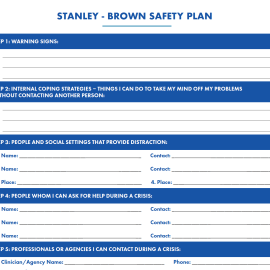

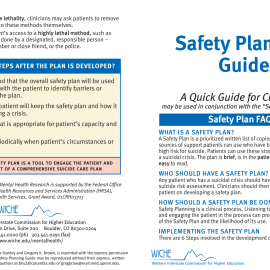

A safety plan is a prioritized written list of coping strategies and sources of support developed by an individual at risk for suicide in collaboration with a clinician. Research shows that individuals with higher-quality safety plans are less likely to be hospitalized in the year after safety planning.1 2Creating unique, customizable safety plans collaboratively rather than presenting a predetermined list of options allows the resource to be tailored to the individual’s needs, comfort, and strengths. It recognizes the individual’s autonomy and expertise on what they find helpful and allows room for adaptations a provider may not have considered.

When creating a safety plan, it is essential that a provider recognize the importance of multicultural humility; what works as a safety measure for one person may not work for another for a multitude of reasons. Providers should enter into the safety planning process with an open mind and sense of curiosity, while also providing knowledge of support measures that have helped others historically.

A safety plan should:

- Be written in the individual’s own words and be easy to read.

- Actively involve the individual’s support systems such as family and friends in the collaborative process, especially to establish their role in responding to times of crisis.

- Be grounded in trauma-informed and recovery orientated approaches, including not assuming families are safe and supportive and that crisis centers are not inherently safe and may lead to police interventions.

- Include counseling on access to lethal means, which is also balanced with respect to legal and ethical requirements under federal and state laws.

- Be revisited and updated regularly and collaboratively during encounters.

- Be in the individual’s possession.

Formats and Protocols

Discussing available formats for the safety plan with the individual allows them to receive a copy in the way in which they are most likely to access it and make use of it. For some, a paper copy may be most useful, while for others, providing information and assistance in accessing electronic or application-based safety planning tools such as the Safety Plan Mobile App or having them take a photo of it to have on their phone would be best.

Regardless of the format the individual chooses, the provider should have a documented copy of the safety plan. Clear protocols should be in place for uploading the safety plan into the electronic health record (EHR), as well as expectations that providers working with individuals for the first time review existing safety plans on file. This helps ensure smooth transitions of care and reduces the need for an individual to repeat themselves. The document should be updated in the EHR each time it is updated with the individual. Organizations should consider having a specific template for the safety plan clearly linked in the individual’s file, ensuring it is easily accessible in times of crisis.

Staff should be trained in creating safety plans, engaging the individual at risk for suicide and any necessary support people, and documenting and following up on the safety plan. It is important to follow up and conduct internal reviews of staff use of safety planning interventions to determine effectiveness, consistent application, and fidelity of this evidence-based practice, and the need for additional staff training or education.

When deciding on the basic structure of the safety plan as well as the clinical process of creating one, the organization should ensure the input of people with lived experience should be centrally incorporated. In addition, receiving feedback from individuals at risk for suicide about their experience with the organization’s safety planning processes should be prioritized as critical perspectives.

Safety planning is not to be confused with contracts for safety or no-suicide contracts. There is no evidence that these contracts are effective; they can increase a sense of stigma and shame for the individual and create a false sense of security for the provider.3, 4 Crisis response planning or safety planning have been found to be more effective than a contract for safety.5 6

Questions to consider:

- What specific safety planning protocols does my organization have?

- How are staff trained in these protocols?

- How are the perspectives of people with lived experience incorporated into this process?

- What local crisis resources can be included?

- How is lethal means safety incorporated into the safety plan?

Suggested Resources

- 1Stanley, B., & Brown, G.K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256-264.

- 2Stanley, B., Chaudhury, S. R., Chesin, M., Pontoski, K., Bush, A. M., Knox, K. L., & Brown, G. K. (2016). An emergency department intervention and follow-up to reduce suicide risk in the VA: acceptability and effectiveness. Psychiatric Services, 67(6), 680-683

- 3Stanley, B., & Brown, G.K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256-264.

- 4Rudd, M., Mandrusiak, M., & Joiner, T. (2006). The Case Against No-Suicide Contracts: The Commitment to Treatment Statement as a Practice Alternative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(2), 243-251.

- 5Stanley, B., & Brown, G.K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256-264.

- 6Bryan, C. J., Mintz, J., Clemans, T. A., Leeson, B., Burch, T. S., Williams, S. R., & Rudd, M. D. (2017). Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in U.S. Army Soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 264-272. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165032716319474