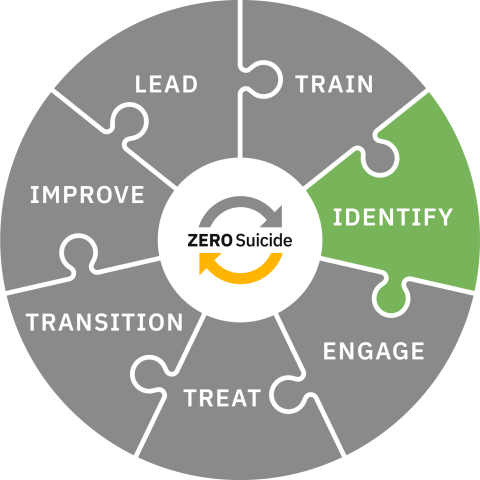

Identify

Identify individuals with suicide risk via comprehensive screening and assessment.

Toolkit

Identify

Identification of Risk

When health and behavioral health care organizations are committed to safer suicide care every new individual to an organization is screened for suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

The purpose of the screening is not to predict suicide but rather to plan effective suicide care. Once a screening indicates some risk for suicide, further information is gathered with the aim of producing a “risk formulation” based on the patient's specific context.1

In a Zero Suicide approach:

- All individuals in care are screened for suicidal thoughts and behaviors at intake and at every subsequent encounter.

- A full assessment of suicide risk is completed at intake to gather information about past suicide thoughts and behaviors and other risk factors.

- Whenever an individual screens positive for suicide risk, an assessment and full risk formulation are completed.

Implementing Suicide Risk Screening

Policies and procedures clearly describe:

- What standard screening tool is used

- Timing and frequency of screening (e.g., at the initial appointment and every appointment thereafter)

- How is the screening provided (e.g., in person, on paper, online/through an app)

- What is a positive screen

- Who reviews the results and determines if further assessment is needed

- How are individuals further assessed (timing, role of assessor)

- How frequently an individual who screens negative is rescreened

- How is screening documented

- How often staff are trained on suicide screening and documentation

- How fidelity is assessed

In inpatient treatment, in addition to the above:

- When individuals are screened during their inpatient stay (i.e., when there is a change in affect or presentation)

- When Individuals are screened prior to discharge

For more discussion about the use of standardized screening tools and information about specific tools, go to the Screening Options tab above.

Implementing Suicide Risk Assessments

Policies and procedures clearly describe:

- What standard assessment tool(s) are used

- Timing and frequency of assessment (e.g., at initial appointment and when there is a positive screen)

- The transition from screening to assessing (i.e., who does what, when, how)

- Who completes the assessment

- How the assessment is documented

- How the assessment tool(s) used connect with the risk formulation

- How often clinical staff are trained on suicide assessment and documentation

- How fidelity is assessed

For more discussion about the use of assessment tools and information about specific tools, go to the Screening tab above.

Implementing Risk Formulation

Policies and procedures clearly describe:

- Timing of initial risk formulation completion (e.g., during the same visit when an individual screens positive)

- Frequency of re-evaluation of risk formulation

- What standard risk formulation model is used

- Who completes the risk formulation/determination (e.g., trained/licensed clinician)

- How clinical staff are trained on risk formulation/determination and documentation (i.e., initial training and refresher trainings)

- How the risk formulation/determination guides treatment decisions

- How the risk formulation/determination is communicated to individuals in care and other appropriate people (e.g., family, support persons).

In inpatient settings, in addition to the above, risk formulation and reassessment are based on multiple, continuous observations, supported by:

- Timely psychiatric consult

- Family member input

- Means-restricted environment

- Up to line-of-sight supervision (or other environmental safety precautions)

- Timely clinical team consultation when increased risk may be present

- Reassessment at discharge and completion of a follow-up post-discharge referral and contact plan

- Multiple observations of reduced risk are required to formally reduce risk status

Click on the Risk Formulation tab above to see an example of a risk formulation model developed by suicide prevention researchers and practitioners.

- 1Pisani, A. R., Murrie, D. C., & Silverman, M. M. (2016). Reformulating suicide risk formulation: From prediction to prevention. Academic Psychiatry 40(4), 623–629. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26667005

Screening for Suicide Risk

Standardized Procedures

In a Zero Suicide approach, procedures to screen individuals for suicide risk are standardized. When procedures are standardized, staff can use the same language to discuss an individual’s risk status and coordinate appropriate care. These are more thoroughly explored below and we include a list of commonly used screening tools.

In a Zero Suicide approach:

- All individuals are screened for suicide risk at their first contact with the organization and at every subsequent contact. All staff members use the same tool and procedures to ensure that individuals at risk of suicide are identified.

Collaboration and Empathy

Screening for suicide risk is more than just asking the right questions in the right order and documenting the answers. As one person with lived experience has stated, "Don’t treat it like a checklist on a clipboard."

When organizations develop a caring, confident, and competent workforce then staff members are comfortable talking with individuals about suicidal thoughts and behaviors. When staff have confidence in their ability to manage an individual’s suicide risk they can determine the least restrictive and supportive environment for the individual.

Training for staff should include:

- How to adopt a collaborative stance that reflects empathy, genuineness, and hope.

- How to create a safe environment so the individual feels able to be transparent about their suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Staff Barriers to Screening

One barrier to consistent screening risk is often about mistaken beliefs about suicide and its causes. The Overcoming Resistance to Zero Suicide activity below can walk through how some of these beliefs might contribute to barriers to suicide risk screening.

Screening

Screening is about standardization. All staff use the same tool and process. The frequency of screening is formalized in a policy/procedure so it is clear to staff when and how to screen individuals in care. This policy does not need to be separate from the rest of the process related to individuals at risk of suicide, but the screening process should be detailed within it.

Screeners vary in the number of questions included. If a screener is used in a medical setting where a full assessment is often done by behavioral health staff (which requires time for a consult), sometimes a secondary screening is also used to determine what level of assessment may be needed.

What “screener” is used will be dependent on the organization, staff, and population needs. See below for a list of commonly used tools for screening for suicide risk.

The SPRC resource Screening and Assessment for Suicide in Health Care Settings provides a comprehensive discussion of the subject, with sections on expert recommendations and how to choose a screening tool.

The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline Suicide Safety Policy, contains suggestions for "prompt questions" (see Appendix B) and other suggestions about eliciting information from individuals who may be at risk for suicide.

Screening Tools

Different organizations and settings use different tools to screen for suicide risk. Which tool is selected depends on who is screening, the setting (e.g., outpatient, inpatient, ED, primary care, etc.) and whether the person screening will follow up with an assessment, if applicable, or if the individual will be transferred to someone else for the assessment. Below are some of the common tools used to screen for suicide risk.

Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ)

The ASQ screening tool was designed for medical settings (e.g., emergency department, inpatient medical/surgical units, outpatient clinics/primary care and specialty clinics) to identify youth at risk for suicide. It was designed to screen youth ages 10-24 but recommends using it for those 10 and younger who present with primary mental health concerns. The ASQ consists of four questions and the tool includes decision-making guidance after a positive result.

All ASQ resources are free and in multiple languages. NIMH has also developed ASQ for youth and adults to be used over telehealth.

The ASQ toolkit includes the Brief Suicide Safety Assessment Guide (BSSA), which incorporates suggestions on what questions to ask, examples of how to respond to and ask questions, and what areas should be explored to develop a fuller understanding of an individual’s suicide risk. It also includes ways to safety plan and counsel about access to lethal means. The BSSA is intended to be used as a secondary screener when an individual screens positive on the ASQ.

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

The C-SSRS offers multiple versions for different settings and populations and has been translated into many languages.

Free Training: There is a free, online course from the New York State Office of Mental Health and Columbia University that provides an overview of the C-SSRS instrument and teaches how and when to administer it.

Computerized Adaptive Screen for Suicidal Youth (CASSY)

The CASSY is a cloud-based universal screening tool that has the capacity for large scale screening in settings such as pediatric hospitals and emergency departments. CASSY can be completed by the youth in typically under 2 minutes and is available in English and Spanish.

Patient Safety Screener-3 (PSS-3)

The PSS-3 is a three-item screening tool for use in acute care settings. It can be administered to all individuals in care, not only those presenting for psychiatric care. The three screening questions pertain to depression, active suicidal ideation within the past two weeks, and lifetime suicide attempt. The tool has been validated for use in the emergency department1 with individuals 18 and older, and has been implemented with individuals 12 and older in both emergency department and inpatient medical settings.

The ED-Safe Secondary Screener-6 (ESS-6) is a 6 question tool that is a secondary screener that is used after a positive screen on the PSS-3. It is intended to help providers determine if a psychiatric evaluation is needed or other safety precautions should be used while caring for the individual. This is intended to be used alongside clinical judgement to plan for an individual’s care.

The Decision Support Tool was developed as an additional screening tool to be used by ED providers with adults. This would be used after an individual screens positive on a brief screening tool (like the PSS-3) and this tool helps providers determine if consultation with a mental health specialist is needed or what other interventions could be helpful.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)

PHQ-9

The PHQ-9 is often used to assess for depression and many organizations use question #9 on this tool as their suicide screening tool. This question asks: “Over the past two weeks, have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?”2

PHQ-A

The PHQ-A was developed for use with adolescents. It measures severity of depression and includes a single question that asks about the presence of suicide ideation in the past month, and any previous suicide attempts.

- 1Boudreaux, E. D., Jaques, M. L., Brady, K. M., Matson, A., & Allen, M. H. (2015). The Patient Safety Screener: Validation of a Brief Suicide Risk Screener for Emergency Department Settings. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(2), 151–160. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1034604

- 2Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Kroenke, K., et al. (2001) Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Retrieved from http://www.phqscreeners.com/sites/g/files/g10016261/f/201412/PHQ-9_Engl…

Assessing Suicide Risk

In a Zero Suicide approach, suicide risk assessment is done by a licensed clinician who has specialized training in assessing the level of suicide risk for individuals. The process of assessment should be standardized and also leave room for clinical judgment.

Organizations should use a standardized tool and/or processes (see below for a list of assessment tools/processes) to guide the clinician through the assessment. This ensures they gather all pertinent information to inform the risk formulation.

The assessment process is not used to predict whether someone is going to attempt or die by suicide, it is to develop the risk formulation that will inform the plan to support the individual.

In a Zero Suicide approach:

- Clinicians conduct a thorough suicide risk assessment when an individual screens positive for suicide risk.1 All staff members use a standardized assessment tool or process to gather relevant information to fully assess an individual’s suicide risk and create a plan to address that risk.

Collaboration and Empathy

Individuals who are experiencing a suicidal crisis are in a vulnerable state and might have fears that they will be involuntarily admitted to a hospital if they share all their suicidal thoughts and actions. It is imperative that clinicians develop a safe environment (physical and psychological). Individuals will then be more likely to engage in the assessment and collaboratively develop the plan to improve their safety.

When organizations develop a caring, confident, and competent workforce then staff members are comfortable talking with individuals about suicidal thoughts and behaviors. When staff have confidence in their ability to manage an individual’s suicide risk they can determine the least restrictive and supportive environment for the individual.

Training for staff should include:

- How to adopt a collaborative stance that reflects empathy, genuineness, and hope.

- How to express understanding of the individual’s ambivalence and that their desire to die is to relieve their intolerable pain.

- Engender confidence that there are alternatives to suicide and how to empower the individual in care to use the available services to help reduce their pain.

- How to treat the screening and assessment process as an exploration of what happened to the individual, not as a task to complete or an examination of what is wrong with the individual.

Information Gathered Through Assessment

There are several aspects to fully assessing for suicide risk which then allows clinicians to develop a risk formulation that will inform treatment planning:

- Gather complete information about present, recent and past suicidal ideation and behavior.

- Gather information about current stressors, relevant risk and protective factors, and history, including treatment history.

- Understand long-term risk factors and ways that impulsivity might impact the individual’s suicide risk.

When assessment is complete the information is synthesized into a prevention-oriented suicide risk formulation anchored in the individual’s life context. The purpose of assessment is not to predict which person might take their own life but to do the best job we can to increase safety, reduce risk, and promote wellness and recovery.

In inpatient behavioral health treatment, the assessment process will be unique to that setting. Even if the admission is not due to suicide risk, the admission process should include a suicide risk assessment. It is important to understand the individual’s history with suicidal thoughts and behaviors as well as other risk factors. Also, it is important that policies and procedures address the frequency of observation, when to rescreen and what prompts a full reassessment.

The SPRC report Caring for Adult Patients with Suicide Risk: A Consensus-Based Guide for Emergency Departments provides comprehensive guidelines for screening and assessment in emergency departments (ED) and offers a quick guide tool for screening and assessment. It recommends asking all individuals reporting suicidal ideation or with suspected suicide risk if they would like a mental health evaluation that includes a comprehensive suicide risk assessment (provided a mental health specialist is available to complete one in a timely manner).

The risk formulation tab further explores how to conceptualize an individual's context and history and synthesize a risk formulation based on multiple points of information.

Billing Codes for Screening and Assessing

Assessing suicide risk takes time and healthcare providers are already struggling to fit everything they need to do into the allotted time. However, there are ways to bill for screening and assessing for suicide risk. The SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions offers a set of state billing and financial worksheets to help clinic managers, integrated care project directors, and billing/coding staff at community mental health centers and community health centers identify the available current procedural terminology codes they can use in their state to bill for services related to integrated primary and behavioral health care. The worksheets can be found in the Tools below. Also, some medical providers are able to use procedure codes for a 15-minutes screen for depression for Medicare patients.

Below are some evidence-based assessment tools and processes that can support clinican’s as they assess the suicide risk of individuals in care.

Assessment Tools

Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk (AMSR)

AMSR is a comprehensive assessment process that identifies an individual's risk of suicide within their own context using a risk formulation that includes the individual's risk status and risk state. It differs from other suicide risk assessments in that it does not include a specific "score" or categorization (i.e., high, moderate, low). AMSR is used in various settings and with different populations and has been validated for ages 12+.

Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation is a brief assessment tool that reviews an individual's thoughts of suicide to identify suicide risk. The full scale assessment tool includes 21 question. It is also available in Spanish.

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

The C-SSRS offers multiple versions for different settings and populations and has been translated into many languages. Some versions are used by organization as a screener and other, longer versions are used as part of an assessment. For example, the C-SSRS screen is a 6 question tool that is often used as a screening too. The C-SSRS Full Scale Lifetime/Recent also includes an exploration of current and lifetime suicidal thoughts (intensity and duration) as well as a thorough examination of the individual’s current and lifetime suicidal behaviors.

Free Training: There is a free, online course from the New York State Office of Mental Health and Columbia University that provides an overview of the C-SSRS instrument and teaches how and when to administer it.

Assessment of Suicidal Risk Using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale

SAFE-T

The SAFE-T is a thorough assessment of the nature and extent of an individual’s suicidal thoughts and behaviors and when used in conjunction with information from other sources is likely to yield the detailed information needed to develop a full picture of an individual’s suicide risk. The items in the SAFE-T explore:

- Ideation: frequency, intensity, duration—in last 48 hours, past month, and worst ever.

- Plan: timing, location, lethality, availability, preparatory acts.

- Behaviors: past attempts, aborted attempts, rehearsals (tying noose, loading gun) vs. non-suicidal self-injurious actions.

- Intent: extent to which the patient, one, expects to carry out the plan and, two, believes the plan/act to be lethal vs. self-injurious. Explore ambivalence: reasons to die vs. reasons to live.

Here is a webinar that explains the SAFE-T and how it was integrated into the Epic EMR.

Risk Formulation

Forming a Clinical Judgment of Risk

Clinicians are often faced with having to make judgment calls about suicide risk with insufficient or contradictory information. Information obtained in a suicide screen is just one part of what is needed to fully assess risk and develop the best care plans to engage clients. Establishing a collaborative and shared perspective is essential to obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the client’s suffering and strengths.

One prevalent method of assessment attempts to put people into predictive categories such as low, medium, or high risk. Despite many efforts to define these terms, definitions were usually difficult to apply, and the terms lack predictive validity, cross-clinician consistency, and clinical utility in treatment planning.1

The high-medium-low model of formulating risk also was not anchored in a context. One could ask, “high compared to what?” or “low compared to when?” In newer, contextual risk formulation methods, the primary purpose is planning rather than prediction of suicide.1

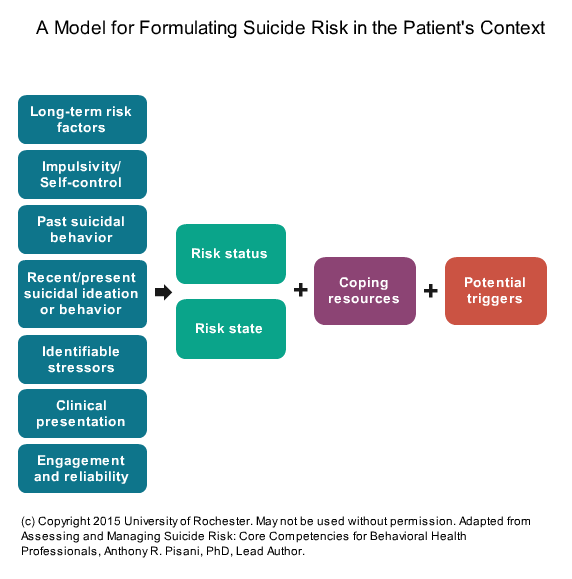

Risk Formulation Model

The model pictured below draws from prevention research and advances in violence assessment.2 While the figure from Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk (AMSR) shows just one way of organizing a risk formulation, the goal is to develop a personalized plan for each individual that is anchored in the clinical or community setting and in the individual’s own history over time. The clinical judgment about risk, combined with the entire formulation, can help with decision-making about what intervention or treatment setting the person needs.

The column at the left in the diagram shows the key information needed to support a risk formulation.

Risk status, risk state, coping resources, and potential triggers comprise the “risk formulation” in this model.

A well-documented risk formulation can demonstrate that clinical decisions were sound and aid in communication with the client, other clinical staff, and important people in the client’s life. Clear documentation also helps to show the rationale behind your formulation, discussions with the client about your risk formulation, and treatment decisions. As new information becomes available and circumstances change, the assessment of risk also should be reconsidered and possibly modified. Clear documentation of risk and the rationale for treatment recommendations will provide a better defense against legal challenges than poor or incomplete documentation.

This interactive is best experienced on desktop browsers and may not work on all mobile devices.

- 1a1bPisani, A. R., Murrie, D. C., & Silverman, M. M. (2016). Reformulating suicide risk formulation: From prediction to prevention. Academic Psychiatry 40(4), 623–629. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26667005

- 2Douglas, K. S., & Skeem, J. L. (2005) Violence risk assessment: Getting specific about being dynamic. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 11(3), 347–383. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.11.3.347

Next Steps

Questions to Answer

Zero Suicide policies, procedures, and processes should answer these questions:

Answering these questions will help you organize your implementation of a screening, assessing and risk formulation process so you can identify individuals at risk of suicide.

Screening

- What prompts a screening? (e.g., initial appointment, every subsequent appointment, change in affect)

- Who is screened? (e.g., every individual under care)

- Who is doing the screening? (e.g., therapist, case manager, nurse)

- What tool are you using to screen? (e.g., C-SSRS screen, ASQ, PSS-3)

- What is the method of screening? (e.g., individual uses a tablet or paper; face to face by a peer, case manager, or licensed clinician)

- At what appointments is the individual screened? (e.g., every appointment including NP/MD, clinician, care manager, peer support, group therapy, LPN/RN)

- What happens when an individual has a positive screen? (e.g., who assesses if different than who/how screened, detail the process to transfer to person who will assess)

- What are documentation requirements? (e.g., the screener embedded in the EHR, included in a progress note)

- Are providers of care able to view prior screen and assessment results? (to be able to see documentation of previous suicidal thoughts/behaviors)

Assessing

- Who are you assessing? (e.g., only those who screen positive, all new individuals)

- Who does the assessment? (e.g., licensed therapist, nurse, psychiatrist)

- What prompts an assessment? (e.g., positive screen, initial intake, after inpatient, suicide attempt)

- With what are you assessing them? (e.g., SAFE-T and the process of gathering additional information)

- What are documentation requirements? (e.g., the assessment tool is embedded in the EHR, the assessment process is detailed in a progress note)

- How does the assessment fit into the plan for managing the individual’s suicide risk?

Risk Formulation

- What is the process for determining risk?

- How does the risk formulation connect to the plan for the individual’s safety and care?

- How are the process of formulating risk and the determined plan of action documented? (with the documented assessment information)

Question

How are you tracking fidelity to your screening, assessing and risk formulation policies and procedures?

Planning Next Steps

Also, determining the screening, assessing and risk formulation processes will connect with how the care pathway works. For more about the care pathway see the Engage element.

There are several additional items to help you plan these next actions:

Quick Guide to Getting Started with Zero Suicide

This one-page tool lists ten actions you can take to start implementation of Zero Suicide.

Getting Further with Zero Suicide

This tool lists several actions you can take if you have been implementing Zero Suicide for a while and are not sure what to do next or need help taking your Zero Suicide work a little further.

Zero Suicide Organizational Self-Study

Every organization should complete the self-study as one of the first steps in adopting a Zero Suicide approach. While the self-study is available in the Lead section of the Zero Suicide online toolkit, it’s provided again here for your convenience.

Zero Suicide Work Plan Template

This form contains an expanded list of action steps to guide your implementation team in creating a full work plan to improve care and service delivery in each of the seven core Zero Suicide components.