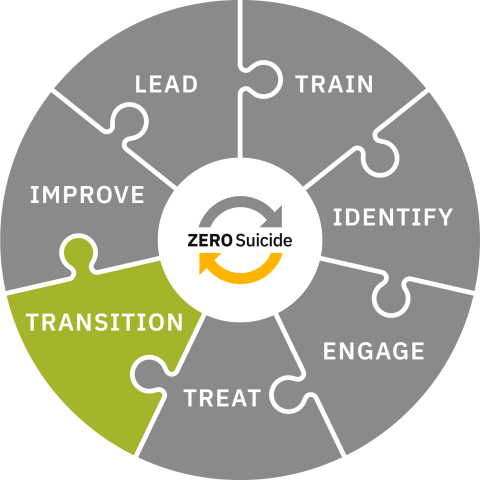

Transition

Transition individuals through care with warm hand-offs and supportive contacts.

Toolkit

Transition

Transition with Care

In a Zero Suicide approach, careful attention is paid to the transition of individuals at risk of suicide between providers of care. Statistically, the transition period with the highest risk is between inpatient and outpatient care, however, each transition is a vulnerable time and requires careful planning to make sure individuals receive the care they need.

Inpatient to Outpatient Care

The period of time after an individual is discharged from inpatient for psychiatric and connected to outpatient care is a vulnerable time for people who are at risk for suicide. There is a 300% increased risk for suicide in the week after discharge from a psychiatric inpatient stay and a 200% increased risk for suicide in the 30 days after discharge.1 It did not matter what the diagnosis was. Even if someone was admitted for psychosis, their risk for suicide increased after discharge.1

The transition from the emergency department (ED) to behavioral health care is another critical transition. Individuals who go to the ED for suicidal thoughts or behaviors need to be carefully assessed and transitioned to the appropriate level of behavioral health care based on their risk level and needs. However, there are unique barriers in an ED which depend a great deal on available resources (e.g., staffing, transportation, community behavioral health providers, and other referral resources). However, it is imperative that providers carefully and completely bridge the transition from inpatient psychiatric care or the ED to outpatient behavioral health care and we discuss strategies in the other tabs set out above.

Here are some additional resources for inpatient to outpatient and ED to outpatient transitions:

- Action Alliance's Best Practices in Care Transitions for Individuals With Suicide Risk: Inpatient Care to Outpatient Care

- Utah Zero Suicide Learning Collaborative – Safe Care Transitions for Suicide Prevention

- Guidelines for integrated suicide-related crisis and follow-up care in Emergency Departments and other acute settings

Other Transitions

There are other important transitions too. For example, the period between a primary care visit and an appointment at behavioral health outpatient services can also be risky. There aren’t statistics on successful or unsuccessful referrals from primary care to outpatient treatment, but we know that strong links between them need to be built for safe and certain transitions for individuals with suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors. We do know that close to 30% of people who die by suicide visited a healthcare provider in the week prior to their death.2

Some examples of other transitions to prepare for:

- When the individual is referred to a provider or service within or outside of the organization (i.e., therapist refers to psychiatric provider, current therapist leaves and the individual is transferred to a different therapist, referral for parenting or peer support, from substance use treatment to mental health treatment, referral to vocational organization, etc.)

- When an individual transitions to another organization or provider in the community (i.e., clinic to clinic, outpatient to partial hospitalization program, respite to outpatient)

- When an individual ends services, either independently or in agreement with the care provider

- Following an individual’s contact with crisis services when a referral for additional care was made

Creating successful bridges in care can be a difficult and confusing process. It is essential that health and behavioral health care systems develop clear protocols and procedures that carefully engage individuals at risk of suicide, so those individuals make and keep the appointments that support their care. Effective care transitions are the responsibility of the provider, not the individual or their family members.

In a Zero Suicide approach:

- Organizational policies provide clear guidance for successful care transitions and specify the contacts and supports needed throughout the process to manage the transitions.

- Staff are provided training (initial and ongoing) appropriate for their role, on the importance of transitions and the organizational procedures to support transitioning individuals.

- Care transition activities (e.g., phone calls to the individual or collaborating providers, postcards sent, and responses) are recorded in the organization’s health record.

- Data are collected to identify gaps in care or training to continuously improve the processes and procedures regarding transitions of care.

- A Just Culture spirit is maintained, particularly if there is an adverse event, and a systems-improvement focus is kept instead of a culture that faults individual service providers.

- Leaders facilitate MOUs or other collaborative relationships between their organization and other organizations to improve the processes of interorganizational transitions.

- Caring contacts are used with appropriate transitions (e.g., inpatient to outpatient, clinic to clinic).

Consider the following research findings:

- A study that looked at data across 33 states found that if a young person was seen by a mental health provider within seven days after discharge from a psychiatric inpatient stay their suicide risk was reduced.3

- Delays in follow-up care were related to the following characteristics: medical comorbidities, Black race, older age, shorter hospital stay, lack of previous mental health care, and managed care.3

- Brief interventions such as safety planning, caring contacts, and care coordination reduced subsequent suicide attempts for individuals who presented with suicidal thoughts or behaviors in an ED or other medical environment.4

- Strategies such as the use of technology, multidisciplinary team approaches, and co-locating medical and behavioral health providers can be helpful to bridge care, particularly for rural populations.5

At the tabs above, you’ll find information about specific transition strategies and the role of crisis center services in ensuring safe care transitions. For more information about the evidence supporting care transitions, please see the Evidence Base section of this website.

- 1a1bChung, D., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Wang, M., Swaraj, S., Olfson, M., & Large, M. (2019). Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open, 9(3), e023883. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023883

- 2Ahmedani, B. K., Westphal, J., Autio, K., Elsiss, F., Peterson, E. L., Beck, A., Waitzfelder, B. E., Rossom, R. C., Owen-Smith, A. A., Lynch, F., Lu, C. Y., Frank, C., Prabhakar, D., Braciszewski, J. M., Miller-Matero, L. R., Yeh, H.-H., Hu, Y., Doshi, R., Waring, S. C., & Simon, G. E. (2019). Variation in Patterns of Health Care Before Suicide: A Population Case-Control Study. Preventive Medicine, 127, 105796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105796

- 3a3bFontanella, C. A., Warner, L. A., Steelesmith, D. L., Brock, G., Bridge, J. A., & Campo, J. V. (2020). Association of timely outpatient mental health services for youths after psychiatric hospitalization with risk of death by suicide. JAMA network open, 3(8), e2012887-e2012887

- 4Doupnik, S. K., Rudd, B., Schmutte, T., Worsley, D., Bowden, C. F., McCarthy, E., ... & Marcus, S. C. (2020). Association of suicide prevention interventions with subsequent suicide attempts, linkage to follow-up care, and depression symptoms for acute care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry, 77(10), 1021-1030.

- 5LeCloux, M. A., Weimer, M., Culp, S. L., Bjorkgren, K., Service, S., & Campo, J. V. (2020). The Feasibility and Impact of a Suicide Risk Screening Program in Rural Adult Primary Care: A Pilot Test of the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions Toolkit. Psychosomatics, 61(6), 698–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2020.05.002

Best Practices

Ensuring Safe Care Transitions

Effective care transition practices require innovative approaches to create an experience of smooth and uninterrupted care from one setting to another. We know that the first few days after discharge from an inpatient psychiatric facility are the riskiest time for individuals, particularly if they have had a recent suicide attempt. It is important to “narrow the gap” between care environments as much as possible -- and that can be difficult when there are availability and access issues. However, there are many actions that can be taken to help support individuals at risk of suicide during times of transition.

Inpatient to Outpatient

Specifically, the referring inpatient provider should:

- Collaboratively revise the individual’s safety plan before discharge

- Provide lethal means counseling or review plan to reduce access to lethal means before discharge (i.e., particularly related to firearms and any medication provided to the individual

- Encourage participation from family or other supportive persons who can help the individual in the intervening time until their appointment with their new provider

- Obtain releases of information from the individual for the new provider and any other supports to facilitate the transition and address any barriers

- Include a peer specialist, if available

- Ensure the individual has had direct contact with the new provider through a warm handoff and has all pertinent information to attend the appointment (e.g., date, time, transportation

- Send records to the new provider several days in advance of the appointment

- Provide a caring contact within the first 24 hours following discharge

- Contact the individual within 24-48 hours after their appointment with new provider to ensure they have transitioned and document the contact

Other Transitions

Other referring providers (e.g., primary care to behavioral health, clinic to clinic, program to program) should:

- Collaboratively update the individual’s safety plan before referral (if a safety plan was done)

- Provide lethal means counseling or review plan to reduce access to lethal means before discharge (i.e., particularly related to firearms and any medication provided to the individual)

- Obtain release of information from individual to enable direct communication, if necessary, between the referring and new provider

- Ensure the individual has had direct contact with the new provider through a warm handoff

- Address any potential barriers to attending the appointment with the individual (e.g., transportation)

- Send records to the new care provider several days in advance of the appointment

- Contact the individual and/or the new provider within 24-48 hours to confirm transition and document the contact

- Follow up with the individual if the appointment was not kept and provide additional support, address barriers, etc.

Also, every step of the care transition process should be properly categorized and documented in the referring and receiving organizations’ records. It is helpful for the triage process and for data collection to identify the type of referral in the EHR (e.g., hospital discharge, step-down transition). This can help staff provide the right level of triage, screening, and assessment at the initial appointment. Any records that are received from referring organizations should be readily available to the receiving provider, preferably in the EHR, so they can be reviewed prior to the first appointment. If a release of information is not included with the records, the receiving provider should obtain one from the individual to ensure permission for any further communication between providers.

Recommended Evidence-Based and Best Practices

Warm Hand-Off

The goal of a warm hand-off is to increase the likelihood that an individual will attend and engage in treatment with the new provider. A warm hand-off can reduce anxiety, calm fears, and create a human connection before the individual even connects with the new provider’s office.

“Look at each step or practice as part of a larger, holistic approach to working toward the health and safety of each patient by cultivating connections. Encourage contact between the outpatient provider and the patient prior to discharge. Find ways to build connections among the patient, family, and the natural supports."

—Best Practices in Care Transitions for Individuals With Suicide Risk, Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention

Rather than simply providing the name and phone number of a provider and leaving it up to the individual to schedule their follow-up care, as happens frequently, a warm hand-off connects the individual with the new provider before discharge. This can be done in a number of ways. An inpatient staff member can call the new provider with the individual and facilitate the follow-up appointment. This way any known barriers to attending the appointment can be addressed immediately. Some facilities have peer support workers who can be an intermediary for individuals who are uncomfortable making and attending an appointment at a new provider, particularly if this is their first time attending outpatient behavioral health treatment. The peer support worker can facilitate the warm hand-off or provide support to the individual throughout the transition process. Hospital Sisters Health System & Prevea Health uses a creative warm hand-off process that includes showing recorded video messages from outpatient providers at the receiving organization to individuals who will be transitioning from inpatient to outpatient care.

Listen to Executive Director of Behavioral Health and Zero Suicide Institute faculty member Toni Simonson speak about this process below:

Rapid Referral and Follow-Up

Rapid referral and follow-up involve taking steps during an emergency department visit, primary care visit, or before discharge from inpatient care to facilitate immediate access to an outpatient treatment appointment, preferably within 24-48 hours after referral or discharge. It is helpful if there is a collaborative agreement between providers that formalizes procedures and expectations. Organization policies should establish processes for:

- Scheduling the first outpatient appointment before discharge if the outpatient provider is reachable.

- Leaving a message with the outpatient provider to request an appointment upon discharge if the provider is not reachable. There should be guidelines for following up with the receiving provider after leaving this message to ensure there is a solidified next step in care for the individual at risk of suicide.

- The organizations should clarify who is responsible for questions or medication issues between discharge and the first appointment with the new provider.

Caring Contacts

Caring contacts are brief communications with individuals during care transitions. These contacts demonstrate continued support from care providers. They can strengthen an individual’s sense of connection to their care which can increase their collaborative participation. Caring contacts may be especially helpful for individuals who have barriers to accessing outpatient care. They should include supportive messages that do not require the individual to do anything. They aren’t a reminder to attend an appointment, or take medication, or use their safety plan. They are simple messages reminding the individual that there are people who care about them. Examples of caring contacts include:

- Postcards, letters, e-mail messages, voice mail messages, and text messages.

- Phone calls made by clinical or non-clinical staff, including peers who have experienced a suicide attempt. Individuals making phone contacts must be trained.

- Caring contacts are best sent from staff who the individual interacted with during the episode of care. It’s important that they are genuine, personalized messages of support and caring.

Here are some examples of caring contacts:

Other Bridging Strategies

The following are more examples of transition strategies:

- Brief education that helps individuals at risk of suicide understand their risks and the importance of follow-up care.

- Peer navigators who can assist individuals who are traversing the system of potential behavioral health supports. Sometimes it’s called peer- or community-bridging.

- Meetings or conversations with family members or other supports preferably prior to discharge to discuss the plan for the time period between care.

- Crisis service providers who provide support between appointments or episodes of care and can assess if acute care is needed at that time

Role of Crisis Services

Using Crisis Services to Augment Care

Prior to 2000, there were several hundred local crisis call centers across the country, underfunded, fragmented, and lacking in credibility with policymakers and funders. Staffed with dedicated volunteers, these poorly funded programs lacked the technology, data-tracking tools, and consistent protocols needed to effectively perform their work.

The nation’s approach to crisis call centers received a significant upgrade starting in 2004 with the creation of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and then in July 2022 with the launch of 988. Comprehensive crisis systems are necessary to prevent avoidable tragedies and to orchestrate effective care and 988 gives federal focus and funding to help to raise the bar on crisis system functioning and to strengthen the entire mental health system.

Providers of crisis care tighten the web of care by aiding individuals who are between episodes of care (e.g., transferring from clinic to clinic), levels of care (e.g., inpatient to outpatient), or appointments. They offer additional support to individuals 24/7/365.

Defining Crisis Services

In the field of suicide prevention, the term crisis services has often meant a hotline or helpline model of care, such as 988, counselors staffing phone lines or, increasingly, text or chat lines (including 988) that assist callers with a suicidal or behavioral health crisis. Organizations that provide support during crises are varied and can include:

- Mobile mental health crisis teams

- First responders

- Walk-in crisis clinics

- Hospital-based psychiatric emergency services

- Mental health respite services

- Peer-based crisis services

- Other programs designed to provide immediate assessment, crisis stabilization, and referral to an appropriate level of ongoing care

Incorporating Crisis Services

Providing a full range of crisis services can reduce involuntary hospitalizations and suicides when paired with mental health follow-up care. Communities should offer a full continuum of services designed to provide the right care at the right time and support an individual’s ability to cope with suicidal thoughts or feelings. This is clearly easier for larger communities with more resources to provide such care, however, there are things that under-resourced communities can do to increase the support that crisis services can provide. Page 35 of SAMHSA's National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Care has information to assist rural areas.

To incorporate the use of crisis services, health and behavioral health organizations should:

- Reach out to crisis organizations and develop collaborative relationships that can be formalized with agreements or subcontracts.

- Provide written information about available crisis services (including 988) to every individual at risk of suicide as part of a safety plan and at discharge from treatment

- Explain the purpose, utility, and services offered by the different crisis services to every individual in care and their family, both at the start of treatment, during times of crisis, and at discharge

- Consider formalizing a relationship between outpatient behavioral health providers and crisis organizations to communicate and collaborate on the care of individuals who are accessing crisis services between appointments. Formalized relationships can enable specific communication about the reasons and outcomes for individuals who access crisis services in these circumstances, and it can strength the entire care continuum

- Consider obtaining consent from individuals prior to their discharge from inpatient or emergency department care for a crisis center to provide follow-up support

You can review the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline Suicide Safety Policy here.

Next Steps

Transition Processes

This page is broken into sections for those who are at the beginning of implementation, in the middle of it, or have been implementing Zero Suicide for a while and need some suggestions on how to fine-tune it at their organization.

Implementation Process: Beginning

One thing you can start with is to outline your goals for improving transitions (short, mid-range, and long-term goals). If you know where you want to go, it can be easier to create the directions to get there. Here are some examples:

Inpatient providers:

- Reduce re-admission rates

- Increase rates of connection to outpatient services after discharge

- Increase individual feelings of hopefulness and being cared about

Outpatient providers:

- Improve "show" rates for individuals recently discharged from inpatient facilities

- Improve collaboration between crisis and outpatient providers

- Decrease client rate of inpatient admissions

Assessment of Available Resources

After you list out your goals, you can do an “environmental scan” of what resources (including relationships) you already have that can help you reach those goals. Here are some examples of what might already be available:

Inpatient providers:

- Good relationship with two outpatient providers

- Leaders are committed to Zero Suicide

- Staff want to be involved

Outpatient providers:

- Already have a MOU with a crisis call center

- Leaders have reached out to inpatient providers to establish formal relationships

- Staff are committed to improving relationships with crisis providers

Deciding What's Next

Once you decide what is the first “stop” in your care transitions journey then map out “who” needs to do “what” to make it happen. Include every role that will have to stop doing something or start doing something.

The following are examples of an intervention and a few of the things that may need to be done to implement that intervention. Your organization will be different.

Implement Caring Contacts (inpatient provider example)

- Clinical staff (who) will decide on the type of card that will be sent (what)

- Supervisors will train clinical and support staff on their roles

- Support staff will order cards, address, and mail the cards

- Leaders will review and approve the additional expense

- Clinical staff members will write notes during team meetings for individuals who were recently discharged

- Support staff will document in the individual’s chart

Rapid Referral (outpatient provider example)

- Leaders (who) review current process for referrals from inpatient providers (what)

- Leaders and providers determine what is preferable and feasible for rapid referrals from inpatient

- Leaders meet with inpatient providers to discuss process

- All staff meet to discuss process changes (include brainstorming activities and feedback)

- Implementation team, or subcommittee, determines the final process for rapid referrals

Implementation Process: Middle

We often think of training as the solution to every implementation problem, and while training is a necessary, people need more than training to change and sustain new behavior. No matter your organization, if you’ve started to implement an intervention or program (e.g., caring contacts, rapid referral and follow-up, educating individuals, collaborating with supports) and you are experiencing difficulties you want to step back and assess the barriers to implementation.

These can be barriers or facilitators to implementation, but if you are already implementing and have hit some roadblocks it might be helpful to focus on finding and overcoming barriers. These can be individual, team, organization, or overall system barriers,1 such as:

Individual

- Belief about consequences (“I’m afraid I’ll get in trouble”)

- Belief about capabilities (“I don’t feel like I can do this”)

- Memory, Attention and Decision Processes (“I can’t remember how to do the new procedure”)

See more individual barriers here.

Team

- Lack of formal and informal leadership support (this could be related to formal/informal leaders or overt/covert words and behaviors of leaders)

- Negative past experiences of change (“the last time we had a project it didn’t work out so well”)

- Insufficient mechanisms for embedding change (lack of support, policies, training procedures)

Organization

- Lack of a “Just Culture” (organization blames individuals for errors and doesn’t take a system level view of errors)

- Lack of alignment in organizational priorities around care transitions (there are no policies supporting care transitions)

- Absorptive capacity (“we’re doing too much right now and can’t add anything else”)

System

(This is usually the external system that impacts your organization.)

- Regulatory bodies (peer support isn't funded through insurance)

- Environmental (in)stability (“we’re mostly grant funded and can’t keep a steady stream of financial support”)

- Reviewing different categories of barriers can help you figure out the significant things that are preventing you from making progress towards your goals and can help you strategize ways to overcome or reduce the barriers’ impact.

Other Suggested Improvement Activities

- Develop internal written policies and procedures that detail out the steps in a transition

- Develop contracts or MOUs with outside organizations, including local crisis centers, to develop procedures to ensure safe care transitions between levels of care and organizations

- Determine the type and frequency of training needed for staff to understand and implement the organization’s policies and procedures for safe care transitions

- Develop short-cuts (1-pager) to remind staff of proper policy and procedure on transitions

- Be collaborative with the individuals in your care when you develop their transition plans

- Be transparent about the requirements and limitations of the organization or providers

- Discuss their choices and support their decisions

- It is important that the individual understands the model of care and the rationale for next steps as they move from one form of care to another

- Monitor to ensure that care transitions are documented and flagged for action in an electronic health record or a paper record (i.e., EHR notifications if an individual who was recently discharged from a psychiatric hospital does not attend a scheduled appointment)

Planning Next Steps

There are several additional items to help you plan these next actions:

Quick Guide to Getting Started with Zero Suicide

This one-page tool lists ten actions you can take to start implementation of Zero Suicide.

Getting Further with Zero Suicide

This tool lists several actions you can take if you have been implementing Zero Suicide for a while and are not sure what to do next or need help taking your Zero Suicide work a little further.

Zero Suicide Organizational Self-Study

Every organization should complete the self-study as one of the first steps in adopting a Zero Suicide approach. While the self-study is available in the Lead section of the Zero Suicide online toolkit, it’s provided again here for your convenience.

Zero Suicide Work Plan Template

This form contains an expanded list of action steps to guide your implementation team in creating a full work plan to improve care and service delivery in each of the seven core Zero Suicide components.

- 1Harvey, G. & Kitson, A. (2015). PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science, 11(33). Open Access: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012…)