Treat

Treat suicidal thoughts and behaviors using evidence-based treatments.

Toolkit

Treat

Interventions & Treatments

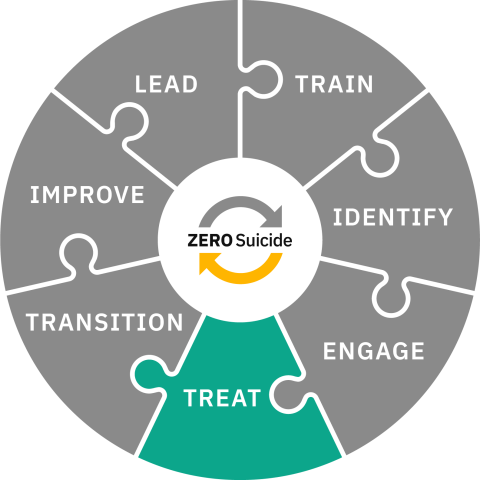

Once your system or organization has plans to identify, screen, and assess individuals at risk for suicide, the next step is to provide evidence-based (or empirically supported) and culturally appropriate interventions and treatments.

In a Zero Suicide approach:

All individuals with suicide risk, regardless of setting, receive interventions and treatments that directly address suicidal thoughts and behaviors (and if applicable and appropriate, also receive treatment for other behavioral health issues). Individuals with suicide risk are collaboratively engaged and offered treatment in the least restrictive setting possible.

Effort is made to find or adapt interventions and treatments to be culturally appropriate for the individual in care. Cultural humility should be the foundation of any treatment provided. Historically, health and behavioral health care providers believed that the most effective way to address suicidal thoughts and behaviors was to address underlying mental health concerns, such as depression or anxiety. The assumption was that resolving these would decrease or eliminate suicidality.1

However, the research strongly supports addressing and treating suicidal thoughts and behaviors specifically and directly, independent of any additional diagnosis or challenge.2 Solely focusing on the “underlying” mental health concern misses any independent suicidality treatment needs. Further, it ignores that while suicide can be a result of mental health disorders, it can also be brought on or exacerbated by other factors including societal hardships or relationship challenges.

Fortunately, interventions and treatment specifically for suicide have been developed and are being increasingly used in the mental health field. They have typically been tested in a variety of settings under various circumstances and have shown benefits (e.g., symptom reduction, increased wellness) among participants. In addition, there have been numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses published discussing best practices for treating suicidal ideation and reducing suicidal behaviors.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Multicultural-Responsive Care

It is important to note the field of suicide prevention is lacking cultural adaptations of evidence-based and empirically supported treatments and interventions.8 Studies have shown these to be highly effective in reducing suicide risk in some populations. However, when selecting a treatment approach, it is important to examine which populations were included in the study.

This does not mean these approaches are only useful among these populations. It often means that the research has not been conducted with a particular population (i.e., Black, Asian, autistic, transgender, etc.) in mind or these groups have not been well represented in research studies. The intervention or treatment could work well with a variety of populations if used in ways that honor and respect the cultural context of the individual. It is important for providers to ensure that any treatment or intervention is culturally resonant and tailored to the individual in care.

Lived Experience

When considering approaches to treatment, it is important to center the voices of those with lived experience. This includes people who have struggled with suicidal thoughts and behaviors as well as those who have supported loved ones at risk or lost loved ones to suicide. There should be lived experience representation on the implementation team. These members should be a key part of the conversation regarding treatment.

First-hand accounts about what treatment methods have been helpful and which have been harmful can be pivotal to a provider’s ability to provide meaningful support to individuals experiencing suicide intensity. While it is important that the treatment approach used is evidence-based/empirically supported, it is also important that its efficacy extends beyond the research and into lived experience.

Other sections include information about least restrictive care, interventions, and treatments to directly and indirectly treat suicidal thoughts and behaviors and reduce suicide risk, and what next steps you can take whether you are beginning implementation of Zero Suicide or want to further your implementation.

Research Base of Interventions and Treatments

Suicide prevention researchers spend much of their time determining what works best for individuals at risk of suicide. They study which interventions and treatments work best for who and where (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, adolescents, adults, etc.). Some interventions and treatments have been studied extensively and have multiple rigorous studies that show they work, and who they work for, and where they work. But there are also interventions and treatments that have emerging research with approximately one to three studies that might not be as rigorous.

In addition, emerging research often has not been tested in multiple settings with different populations. It does not mean they do not work in those settings or with those populations, just that they have not been tested, so those questions remain unanswered. Organizations need to choose the interventions and treatments that work best for their staff and individuals in their care. Sometimes the most evidence-based intervention or treatment is not the best fit for an organization’s staff or clients.

In the Direct Care and Indirect Care tabs we have listed here multiple suicide-specific treatments and interventions. Some are considered evidence-based (multiple studies with high rigor) and other are considered empirically supported (fewer studies, potentially less rigor). Also, please note that the supportive research for each intervention or treatment is not always included. The research is constantly evolving and there are nuances within research studies that space precludes us from elaborating on the research for each intervention and treatment. Feel free to review the Evidence Base section of this website for overall research that supports suicide-specific treatment.

- 1Brown G. K., & Jager-Hyman S. (2014). Evidence-based psychotherapies for suicide prevention: Future directions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3 Suppl 2), S186–194. Retrieved from http://actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/sites/actionallianceforsui

- 2Ellis, T. E., Rufino, K. A., Allen, J. G., Fowler, J. C., & Jobes, D. A. (2015). Impact of a suicide‐specific intervention within inpatient psychiatric care: The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 45(5), 556-566. Retrieved from https://blogs.uw.edu/brtc/files/2015/01/Ellis-et-al.2015-CAMS-in-inpati…

- 3A., Oquendo, M. A., Allen, I. E., Franck, L. S., & Lee, K. A. (2016). Direct versus indirect psychosocial and behavioural interventions to prevent suicide and suicide attempts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(6), 544-554.

- 4Fox, K. R., Huang, X., Guzmán, E. M., Funsch, K. M., Cha, C. B., Ribeiro, J. D., & Franklin, J. C. (2020). Interventions for suicide and self-injury: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across nearly 50 years of research. Psychological bulletin, 146(12), 1117.

- 5Zalsman, G., Hawton, K., Wasserman, D., van Heeringen, K., Arensman, E., Sarchiapone, M., ... & Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 646-659.

- 6Sobanski, T., Josfeld, S., Peikert, G., & Wagner, G. (2021). Psychotherapeutic interventions for the prevention of suicide re-attempts: a systematic review. Psychological medicine, 1-16.

- 7Jobes, D.A., Au, J.S. & Siegelman, A. Psychological Approaches to Suicide Treatment and Prevention. Curr Treat Options Psych 2, 363–370 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-015-0064-3

- 8Pham, T. V., Fetter, A. K., Wiglesworth, A., Rey, L. F., Chicken, M. L. P., Azarani, M., ... & Gone, J. P. (2021). Suicide interventions for American Indian and Alaska native populations: a systematic review of outcomes. SSM-mental health, 1, 100029.

Least Restrictive Care

Providing the Least Restrictive Care

Along with the emphasis on treating suicide risk directly, newer models of care suggest that treatment and support of persons with suicide risk should be carried out in the least restrictive setting.1 Interventions should be designed—and clinicians should be sufficiently skilled—to work with the person in outpatient treatment, with an array of supports, and avoid hospitalization whenever possible.2, 3

Stepped-Care Model

A 2014 article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine recommended a “stepped care treatment pathway” for suicide prevention. According to the authors, in a stepped care model for suicide prevention, individuals at risk of suicide are “offered numerous opportunities to access and engage in effective treatment, including standard in-person options as well as telephone, video, web-based, and smartphone interventions.”1 Stepped care has been applied to many health and behavioral health challenges and delivers care by first offering less intensive, often less restrictive interventions and then “stepping up” to more intensive services when clinically indicated. In the video below, David Jobes sets out six levels of care for a stepped care model for suicide risk:

- Crisis center hotline support and follow-up

- Brief intervention and follow-up

- Suicide-specific outpatient

- Emergency respite care

- Partial hospitalization, with suicide-specific treatment

- Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, with suicide-specific treatment

Crisis Support and Follow-Up

In the field of suicide prevention, the term “crisis services” has a broad scope. Crisis services include mobile crisis teams, walk-in crisis clinics, hospital-based psychiatric emergency services, peer-based crisis services, and other programs designed to provide assessment, crisis stabilization, and referral to an appropriate level of ongoing care. These services are particularly helpful for individuals with barriers to accessing outpatient mental health services. They can also serve as a point of contact for individuals between outpatient visits.

Crisis services include care coordination services, which have the potential to lower readmission rates and some can provide follow-up services. Crisis centers that are members of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (988) follow best practices in assessing suicide risk. These centers have access to a national network of crisis center peers and resources. Crisis lines for Veterans, people who are deaf or hard of hearing, LGBTQIA+ individuals, and Spanish speakers are also available. Some crisis lines provide translation for several different languages. Follow-up can include caring contacts in the form of non-demand messages given to individuals through email, mail, phone calls, text messages, or other forms of electronic communication. See the Transition element for more information about incorporating Crisis Services into Zero Suicide.

Brief Interventions and Follow-Up

Brief interventions range from a single, in-person session to a computer-administered intervention in a primary care office to an online screening and feedback intervention that can be done on a smartphone or tablet.6, 7

Brief interventions can be immediate, free-standing interventions or they can be used in conjunction with any other level of care. For example, while best practices emphasize that safety planning is most effective when done as part of a larger treatment plan to address suicide risk, ensuring individuals who decline outpatient care have a safety plan can be instrumental in saving lives. In theory, the delivery of a brief intervention for suicide theoretically requires less training than for more comprehensive treatments such as Dialectical Behavioral therapy or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for suicide prevention. Brief interventions can be inexpensive, and they can be delivered almost anywhere. More information can be found on safety planning in the Interventions tab and within the Engage element.

Emergency Respite Care

Respite care is an alternative to inpatient or emergency department services for a person in a mental health or suicidal crisis when that individual is not in immediate danger. Respite centers are usually located in residential facilities that are designed to feel more like homes than hospitals. They may also include staff members who are peers with lived experience of mental health issues or suicide. Individuals in crisis may prefer such settings.4 Respite care has shown better functional outcomes than acute psychiatric hospitalization and may include the following:

Assistance with providing continuity of care and establishing longer-term support resources Provision of phone, text, or online virtual supports for an individual before and/or after a stay Evaluation of the development, operation, and outcomes of services provided

Partial and Inpatient Hospitalization

Inpatient hospitalization is generally the most restrictive and costly option for addressing suicide risk. While hospitalization may reduce the risk for suicide while an individual is in care, most inpatient services generally do not include empirically supported suicide-focused care.5 Research suggests that individuals may be at higher risk immediately following discharge from inpatient care.6, 7 Potential reasons for this are complex and varied. Some experts who study suicide have questioned whether aspects of the experience of hospitalization itself may be harmful and increase post-discharge suicide risk.8

Hospitalizations can represent the loss of autonomy for some individuals which can sometimes exacerbate suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Unless the individual is in imminent danger, the decision to seek inpatient care should be collaborative.

Facilitating Less Restrictive Care

Two additional strategies – mobile crisis care and telehealth – can augment any stage of a stepped-care plan. These strategies may help to maintain a person at risk for suicide in outpatient treatment, thus reducing the need for hospitalization.

Mobile Crisis Teams

Mobile crisis teams provide care in the community at the location of the person who is suicidal. Ideally, these teams include peer specialists and members of relevant professional disciplines, including psychiatry, psychology, counseling, social work, and/or case management. Research has shown that mobile outreach can help people address psychiatric symptoms and reduce:

- The number and cost of psychiatric hospitalizations

- The need for law enforcement intervention

- The number of ED visits9

Telehealth

Telehealth uses electronic communication, such as telephone or video, to provide clinical mental health services. Health and behavioral health care organizations can use these services to provide emergency assessments and treatment—particularly for individuals located in remote geographic regions, or with transportation or mobility barriers. Telehealth has been shown to improve outcomes in medical settings for individuals with behavioral health concerns. In addition to emergency assessments, telehealth services can include medication management, clinical therapeutic treatments, and provider-to-provider consultation. Telehealth may also be a good option for healthcare organizations with limited access to mental health resources.10, 11, 12

- 1a1bAhmedani, B. K., & Vannoy, S. (2014). National pathways for suicide prevention and health services research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3 Suppl 2), S222–S228. Retrieved from https://theactionalliance.org/

- 2Ward-Ciesielski, E. F., & Rizvi, S. L. (2021). The potential iatrogenic effects of psychiatric hospitalization for suicidal behavior: A critical review and recommendations for research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 28(1), 60.

- 3Forte, Alberto MD; Buscajoni, Andrea MD; Fiorillo, Andrea MD, PhD; Pompili, Maurizio MD, PhD; Baldessarini, Ross J. MD. (2019). Suicidal Risk Following Hospital Discharge: A Review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27:4, 209-216 doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000222

- 4U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Crisis Services: Effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and funding strategies (HHS Publication No. [SMA]-14-4848). Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Crisis-Services-Effectiveness-Cost-Eff…

- 5Jobes, D. A. (2012), The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS): An evolving evidence-based clinical approach to suicidal risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(6), 640–653. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00119.x/abs…

- 6Bickley, H., Hunt, I. M., Windfuhr, K., Shaw, J., Appleby, L., & Kapur, N. (2013). Suicide within two weeks of discharge from psychiatric inpatient care: A case-control study. Psychiatric Services, 64(7), 653–659. Retrieved from http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ps.201200026

- 7Chung, D., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Wang, M., Swaraj, S., Olfson, M., & Large, M. (2019). Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open, 9(3), e023883. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023883

- 8Large, M. M., & Kapur, N. (2018). Psychiatric hospitalisation and the risk of suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(5), 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.22

- 9U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Crisis Services: Effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and funding strategies (HHS Publication No. [SMA]-14-4848). Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Crisis-Services-Effectiveness-Cost-Eff…

- 10Sullivan SR, Myhre K, Mitchell EL, Monahan M, Khazanov G, Spears AP, Gromatsky M, Walsh S, Goodman A, Jager-Hyman S, Green KL, Brown GK, Stanley B, Goodman M. Suicide and Telehealth Treatments: A PRISMA Scoping Review. Arch Suicide Res. 2022 Feb 9:1-21. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2022.2028207. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35137677.

- 11Godleski, L., Darkins, A., & John Peters, J. (2012). Outcomes of 98,609 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs patients enrolled in telemental health services, 2006–2010. Psychiatric Services, 63(4), 383–385. Retrieved from http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ps.201100206

- 12Hilty, D. M., Ferrer, D. C., Parish, M. B., Johnston, B., Callahan, E. J., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2013). The effectiveness of telemental health: A 2013 review. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 19(6), 444–454. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23697504

Direct Care

Interventions and Treatments that Directly Address Suicidality

To treat suicidal thoughts and behaviors, systems can intervene through “interventions” and “treatments.” Interventions are typically briefer (e.g., one session encounter) and focus on acute crisis stabilization. Treatment modalities can vary from several sessions to several years. Please note that the supportive research for each intervention or treatment is not always included in this tab and within the Indirect Care tab. The research is constantly evolving and there are nuances within research studies that space precludes us from elaborating on the research for each intervention and treatment. Following is a list of interventions and treatments that directly treat suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

A word about the research

Below are listed multiple treatments and interventions. Some are considered evidence-based (multiple studies with high rigor) and other are considered empirically supported (fewer studies, potentially less rigor). Also, please note that the supportive research for each intervention or treatment is not always included. The research is constantly evolving and there are nuances within research studies that space precludes us from elaborating on the research for each intervention and treatment. Feel free to review the Evidence Base section of this website for overall research that supports suicide-specific treatment.

Interventions

Safety Planning

A safety plan is a prioritized written list of coping strategies and sources of support developed for individuals at risk of suicide in collaboration with a mental health provider.1, 2 In a meta-analysis, safety planning-type interventions were shown to prevent future suicide attempts compared to control.2 Safety planning is most effective in decreasing future suicidal behavior and inpatient hospitalizations when it is made collaboratively, is tailored to the unique experiences faced by the individual at risk of suicide,3 and when there is follow-up to update the plan and engage with future care.4, 5 Further, ensuring social contacts are listed in both the distraction and help contact sections has been shown to be crucial for decreasing odds of suicide attempts, emergency department visits, and inpatient hospitalizations in the year following the creation of the safety plan.6 Additional information about safety planning can be found in the Engage section of the Toolkit.

JASPR Health

Jaspr Health is a tablet-based app that provides access to four “evidence-based practices” for individuals who present to the emergency department for suicidal thoughts or behaviors. These individuals can engage with the app while waiting for emergency department psychiatric care. Jaspr Health includes the Collaborative Assessment and Management (CAMS)’s assessment guided by artificial intelligence-powered virtual chatbot that is summarized and provided to the care team, video messages of hope and insights by individuals with lived experience, video messages about navigating the emergency department by individuals with lived experience, and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) skills. A pilot study found Jaspr Health to be feasible, acceptable, and clinically effective for individuals who are acutely suicidal and seeking emergency department psychiatric care.7, 8

Teachable Moment Brief Intervention (TMBI)

TMBI was created for medically hospitalized individuals following a suicide attempt. This intervention has 9 components that are delivered in one 30-60-minute session. Developed based on core components from other suicide prevention interventions (i.e., CAMS, DBT, cognitive behavior therapy for suicide prevention), TMBI focuses on establishing rapport, then identifies drivers for the suicide attempt, engages the individual in a functional analysis of the suicide attempt, and identifies what the individual gained and lost from the attempt. Finally, a short-term crisis response plan and a longer-term treatment plan for recovery are created.

In a pilot randomized controlled trial, individuals at risk for suicide reported high satisfaction and those receiving TMBI were more likely to be motivated and engage in mental health services at 3 months.9, 10

Direct Treatments

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT)

The term dialectical means a synthesis or integration of opposites, and in DBT, it refers to the seemingly opposite strategies of acceptance and change. DBT centers on four core skill areas: mindfulness, emotional regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and distress tolerance.11 DBT has four components, although these may be adjusted in practice to suit specific circumstances:

- A skills training group meeting once a week for 24 weeks

- Individual treatment once a week, running concurrently with the skills group

- Phone coaching, upon request by the individual in care

- Consultation team meetings – a kind of “therapy for the therapists”12

Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS)

CAMS is an intensive suicide-focused treatment to help individuals develop means of coping and problem-solving to replace or eliminate thoughts of suicide as a coping strategy. CAMS focuses on treating suicide ‘drivers’ that make someone want to die and works to strengthen the therapeutic alliance and increase motivation. One of the core values of the CAMS model is that most individuals at risk of suicide can be treated effectively in outpatient settings. When receiving CAMS care, the individual fills out a “Suicide Status Form” (SSF) in collaboration with the clinician during every session to assess risk and document their treatment plan progress.

The “CAMS Stabilization Plan” is also used to reduce access to lethal means and increase coping strategies.13 Additional tools developed in research settings are described in the 3rd edition of the CAMS manual, including a Stabilization Support Plan to be completed with anyone supporting the care of their loved one who is in CAMS care (e.g., parents, spouse).14 CAMS effectiveness is supported by clinical research, multiple correlation studies, and six published randomized controlled trials.15, 16, 12, 17, 18, 19

CAMS-BI (CAMS Brief Intervention) is a clinical, evidence-based approach for managing suicide risk in emergency departments and inpatient units. In a single one-hour session, a trained clinician works with the individual to assess suicidal thoughts, create a safety plan, and develop a follow-up care plan. CAMS-BI is designed to reduce immediate distress and can be used by various mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, and supervised graduate students.

Brief Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Suicidal Ideation (MB-SI)

MB-SI is a brief, manualized intervention developed for Veterans who have been psychiatrically hospitalized. MB-SI includes four 45-minute individual sessions (one session per day, over a range of 12 subsequent days) and mindfulness homework is assigned at the end of each session. A handout reviewing the material covered in the session is also provided. Crisis Response Planning is also included in every session.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide (CBT-SP)

CBT-SP is theoretically grounded in principles of CBT, DBT, and specific therapies for suicidal individuals. It includes the concept of the “suicide mode,”20 and seeks to help individuals learn to recognize this mode, identify triggers, and learn coping skills. During treatment, individuals work on:

- Cognitive restructuring strategies, such as identifying and evaluating automatic thoughts from cognitive therapy.

- Emotion regulation strategies, such as action urges and choices, emotions thermometer, index cue cards, mindfulness, opposite action, and distress tolerance skills from DBT.

- Other CBT strategies, such as behavioral activation and problem-solving strategies.21

There are several iterations of CBT-SP, including information processing biases, appraisals of defeat, entrapment, social isolation, emotional dysregulation, and interpersonal problem-solving suicide schema.

Post Admission Cognitive Therapy

Post Admission Cognitive Therapy (PACT) is an inpatient adaptation for CT-SP. PACT sessions typically include six 60-90 minute sessions of individual psychotherapy over the course of a 3-day hospital stay. The first 1-2 sessions focus on engagement, safety planning, and a cognitive behavioral conceptualization of the recent suicide attempt. The next 1-2 sessions focus on teaching and practicing cognitive behavioral skills. The last 1-2 sessions center on refining the safety plan and a series of relapse prevention exercises to prevent future suicide attempts.

Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for suicide prevention (BCBT) is a shortened version of CT-SP and focuses on the development of a crisis response plan.22, 23

Suicide Prevention Programme

This 8-session for 60-minutes-each, manualized group therapy includes three phases: cognitive reconstruction to overcome suicidal impulses and destructive feelings through, reinforcement of coping skills through behavioral training, and management of suicide risk factors through coping resources.

Survivors of Suicide Attempts (SOSA) Support Groups

SOSA is an 8-session, 60-minute, drop-in support group that included weekly closed groups where suicide attempt survivors discussed suicide triggers and safety plans, community resources, and hope.

Cognitive Behavioral Prevention for Suicide in Psychosis (CBSPp)

Cognitive Behavioral Prevention for Suicide in Psychosis (CBSPp) is a manualized 24-session individual therapy protocol with sessions occurring twice a week.24, 25

- 1Stanley, B., & Brown, G. K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256–264. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-07473-004

- 2a2bNuij, C., van Ballegooijen, W., De Beurs, D., Juniar, D., Erlangsen, A., Portzky, G., ... & Riper, H. (2021). Safety planning-type interventions for suicide prevention: meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 219(2), 419-426.

- 3Gamarra, J. M., Luciano, M. T., Gradus, J. L., & Stirman, S. W. (2015). Assessing variability and implementation fidelity of suicide prevention safety planning in a regional VA Healthcare System. Crisis, 36 (6), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000345

- 4Boudreaux, E. D., Haskins, B. L., Larkin, C., Pelletier, L., Johnson, S. A., Stanley, B., Brown, G., Mattocks, K.,& Ma, Y. (2020). Emergency department safety assessment and follow-up evaluation 2: An implementation trial to improve suicide prevention. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 95, 106075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.106075

- 5Stanley, B., Brown, G. K., Currier, G. W., Lyons, C., Chesin, M., & Knox, K. L. (2015). Brief intervention and follow-up for suicidal patients with repeat emergency department visits enhances treatment engagement. American Journal of Public Health, 105 (8), 1570–1572. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302656

- 6Chalker, S. A., Parrish, E. M., Martinez Ceren, C. S., Depp, C. A., Goodman, M., & Doran, N. (2022). Predictive importance of social contacts on U.S. Veteran suicide safety plans. Psychiatric Services. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100699

- 7Dimeff, L. A., Jobes, D. A., Koerner, K., Kako, N., Jerome, T., Kelley-Brimer, A., ... & Schak, K. M. (2021). Using a tablet-based app to deliver evidence-based practices for suicidal patients in the emergency department: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR mental health, 8(3), e23022.

- 8Dimeff, L. A., Jobes, D. A., Tyndal, T., Zhang, I., Stefan, S., Kako, N., ... & Ilac, M. (2021). Using the Delphi method for determining key performance elements for delivery of optimal suicide-specific interventions in emergency departments. Archives of suicide research, 1-15.

- 9O’Connor, S. S., Comtois, K. A., Wang, J., Russo, J., Peterson, R., Lapping-Carr, L., & Zatzick, D. (2015). The development and implementation of a brief intervention for medically admitted suicide attempt survivors. General hospital psychiatry, 37(5), 427-433.

- 10O'Connor, S. S., Mcclay, M. M., Choudhry, S., Shields, A. D., Carlson, R., Alonso, Y., ... & Nicolson, S. E. (2020). Pilot randomized clinical trial of the Teachable Moment Brief Intervention for hospitalized suicide attempt survivors. General hospital psychiatry, 63, 111-118.

- 11Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT skills training manual (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Retrieved http://behavioraltech.org/resources/whatisDBT.cfm

- 12a12bAndreasson, K., Krogh, J., Wenneberg, C., Jessen, H. K. L., Krakauer, K., Gluud, C., & Nordentoft, M. (2016). Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy versus collaborative assessment and management of suicidality treatment for reduction of self-harm in adults with borderline personality traits and disorder – A randomized observer-blinded clinical trial. Depression and Anxiety, 33(6). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26854478/.

- 13Tyndal, T., Zhang, I., & Jobes, D. A. (2021). The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS) stabilization plan for working with patients with suicide risk. Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1037/PST0000378

- 14Jobes, D. A. (in press). Managing suicidal risk: Third edition: A collaborative approach (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- 15Ryberg, W., Zahl, P-H., Diep, L.M., Landrø, N.I., & Fosse, R., (2019). Managing suicidality within specialized care: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 249: 112-120. https://cams-care.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Ryberg-et-al-CAMS-RCT…

- 16Swift, J.K., Trusty, W.T., and Penix, E.A. (2021). The effectiveness of the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) compared to alternative treatment conditions: A meta-analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12765

- 17Jobes, D.A., Comtois, K.A., Gutierrez, P.M., Brenner, L. A., Huh, D., Chalker, S.A., Ruhe, G., Kerbrat, A.H., Atkins, D.A., Jennings, K., Crumlish, J., Corona, C.D., O’Connor, S., Hendricks, K.E., Schembari, B., Singer, B., & Crow, B. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of the collaborative assessment and management of suicidality versus enhanced care as usual with suicidal soldiers. Psychiatry, 80: 339-356. https://cams-care.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Jobes-Comtois-Gutierre…

- 18Jobes, D. A., Wong, S. A., Conrad, A., Drozd, J. F., & Neal-Walden, T. (2005). The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality vs. treatment as usual: A retrospective study with suicidal outpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(5), 483–497.: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16268766/.

- 19Poston, J. M., & Hanson, W. E. (2010). Meta-analysis of psychological assessment as a therapeutic intervention. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018679

- 20Brown, G. K., Ten Have, T., & Henriques, G. R. (2005). Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 294(5), 563–570. Retrieved from http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/201330

- 21Stanley B., Brown, G., Brent, D. A., Wells, K., Poling, K., Curry J., Kennard, B.D., Wagner, A., Cwik, M.F., Klomek, A.B., Goldstein, T., Vitiello, B, Barnett, S., Daniel, S.& Hughes, J. (2009). Cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBT-SP): Treatment model, feasibility and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(10), 1005–1013.

- 22Bryan, C. J., Mintz, J., Clemans, T. A., Burch, T. S., Leeson, B., William, S., & Rudd, M. D. (2017). Effect of crisis response planning on patient mood and clinician decision making: A clinical trial with suicidal U. S. soldiers. Psychiatric Services, 69(1), 108-111. https://doi.org/10.1176.APPI.PS.201700157

- 23Bryan C. J., Mintz, J., Clemans, T. A. Burch, Leeson B., Burch, T. S., Williams, S. R., Manye, E., & Rudd, M. D. (2017) Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in U. S. Army Soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2017.01.028

- 24Tarrier, N., Gooding, P., Pratt, D., Kelly, J., Awenat, Y., & Maxwell, J. (2013). Cognitive behavioural prevention of suicide in psychosis: a treatment manual. Routledge.

- 25Tarrier, N., Taylor, K., & Gooding, P., (2008) Cognitive–behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Modif. 32 (1), 77–108.

Indirect Care

Interventions and Treatments that Indirectly Address Suicidality

Indirect treatments focus on risk factors related to suicide but do not necessarily target suicidal thoughts and behaviors as part of the treatment. Indirect treatment can be adapted to be direct suicide-focused treatments (see DBT section below). This is not an exhaustive list of all treatments that may decrease thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to suicide. This list of treatments focuses on treatments that target risk factors related to suicide and treatments that specifically address individuals at increased risk for suicide.

A word about the research

Below are listed multiple treatments and interventions. Some are considered evidence-based (multiple studies with high rigor) and other are considered empirically supported (fewer studies, potentially less rigor). Also, please note that the supportive research for each intervention or treatment is not always included. The research is constantly evolving and there are nuances within research studies that space precludes us from elaborating on the research for each intervention and treatment. Feel free to review the Evidence Base section of this website for overall research that supports suicide-specific treatment.

Interventions

Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT)

ABFT is an empirically supported treatment that is personalized, process-oriented, trauma-focused and rooted in attachment theory to target adolescent depression and suicidality with the goal to address attachment ruptures at the core of the family conflict.1 There are five therapeutic tasks in ABFT which are typically covered over 10 sessions:

- Shift the focus from individual symptoms to the individual’s relationships with others

- Build an alliance with the adolescent

- Build an alliance with the parents/guardians

- Assist the adolescent in expressing their grievances to their parents

- Teach and practice relational skills

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

ACT is a mindfulness-based, action-oriented treatment. ACT centers on acknowledging that suffering is part of the human experience and so by remaining in the present moment and accepting thoughts and feelings without the need to become attached to them, judge them, or change them, one can move through difficult experiences and move towards a values-driven life. There are six core components in ACT.

- Cognitive diffusion

- Expansion and acceptance

- Contact with the present moment

- Self as context

- Values

- Committed action

ACT is delivered individually as well as in group therapy formats; it has been shown to be effective for numerous psychiatric conditions.

Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBTI) via Sleepio

Sleepio is a digital application that provides CBTI. In this format of CBTI, individuals have 12 weeks to access 6 sessions of CBTI in which new sessions are “unlocked” each week with the expectation that sessions would be completed 1x/week. Sleepio is fully automated and standardized. The intervention covered behavioral components (sleep restriction, stimulus control), cognitive components (e.g., cognitive restructuring, paradoxical intention), progressive muscle relaxation, and sleep hygiene. Sessions are directed by an animated ‘virtual therapist’ who reviews and guides progress with the individual based on submitted sleep data. Participants are granted access to new sessions weekly (i.e., new session became available a week after completing a previous session).

Mentalization Based Treatment (MBT)

MBT is a psychodynamic treatment rooted in attachment and cognitive theory that aims to strengthen an individual’s capacity to understand their own and other’s states to address affect, interpersonal functioning, and triggers for suicidal behaviors.

Problem Solving Therapy (PST)

PST is a long-standing brief and focused treatment aimed at teaching skills to solve problems. There are multiple manualized versions, versions that include tele-support (e.g., phone calls), as well as brief adaptations. Typically, PST includes some form of teaching individuals how to recognize problems, select a problem to work on, identify solutions, and build an action plant to address the selected problem.

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT)

IPT focuses on providing techniques of interpersonal incident analysis and communication analysis to help individuals identify what contributes to their psychological pain and find ways to express their interpersonal needs to help alleviate suffering. When IPT is focused on those at risk for suicide, the treatment will also include adaptations to focus on the individual’s suicide risk and resiliency factors to help formulate an interpersonal conceptualization.2 3

Group Treatments

The below treatments have emerging research to support them.

Coping, Understanding, Support and Prevention (CUSP) Group

The CUSP Group is a group therapy that functions as a semi-structured, drop-in support group. Sessions last for 60 minutes and during sessions, participants are encouraged to speak about their mood, functioning, suicidal thoughts, and stressors which the two group leaders offer process, support, and education for based on the discussions.

Grady Nia Project (Nia)

Nia is a manualized 10-session, 90-minute group therapy that is culturally informed, based on the theory of triadic influence (TTI).4 Nia provides psychoeducation of the correlation between intimate partner violence (IPV) and suicide, safety planning for suicidal behaviors and IPV, and reducing interpersonal, social, and situational risk factors.5, 6, 7

Interdisciplinary, Recovery-Oriented Intensive Outpatient Program (IR-IOP)

This intensive outpatient program is a manualized, 10-day for 60-minutes-each process-based group therapy including skills, education, and discussion for crisis management, wellness, and coping skills, emotional regulation, and problem-solving. Evidence-based suicide risk and management strategies are also included. This group therapy specifically works with individuals who are at risk of psychiatric hospitalization or re-hospitalization regardless of diagnosis.

Spiritual and Religious Group Psychotherapy

The group is 10 sessions long, for 60 minutes each, and delivered three times a week. The focus was on reading religious scripture and reliance on God and discussing suicide.

- 1Diamond, G., Russon, J., & Levy, S. (2016). Attachment‐based family therapy: A review of the empirical support. Family process, 55(3), 595-610.

- 2Heisel, M. J., Duberstein, P. R., Talbot, N. L., King, D. A., and Tu, X. M. (2009). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for older adults at risk for suicide: preliminary findings. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 40, 156–164. doi: 10.1037/a001473

- 3Heisel, M. J., Talbot, N. L., King, D. A., Tu, X. M., and Duberstein, P. R. (2015). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for older adults at risk for suicide. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 23, 87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.010

- 4Flay, B. R., & Petraitis, J. (1994). The theory of triadic influence: A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. Advances in Medical Sociology, 4,19–44.

- 5Kaslow N. J., Leiner, A. S., Reviere S., Jackson E., Bethea K., Bhaiu J., Rhodes, M., Gantt M. J., Senter, H. & Thompson, M. P. (2010). Suicidal abused African American women’s response to a culturally informed intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(4), 449. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019692

- 6Taha, F., Zhang, H., Snead, K., Jones, A. D., Blackmon, B., Bryant, R. J., ... & Kaslow, N. J. (2015). Effects of a culturally informed intervention on abused, suicidal African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(4), 560.

- 7Zhang, H., Neelarambam, K., Schwenke, T. J., Rhodes, M. N., Pittman, D. M., & Kaslow, N. J. (2013). Mediators of a culturally-sensitive intervention for suicidal African American women. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 20(4), 401-414.

Next Steps

Interventions & Treatments

There are many interventions and treatments to chose from and it is difficult to find the right one(s). Sometimes we pick the ones we are most familiar with and don’t go through a careful process to choose the intervention and treatment that will best suit our organization, staff, and the individuals who rely on you for care.

Here are some questions that can help guide you through the process of choosing the best interventions/treatments.

They aren’t the only questions you can ask, but they are examples. You can use these questions (and the other ones you come up with) to compare the interventions/treatments you are interested in using.

The individuals we serve:

- Who are the individuals we serve? Are they adolescents, adults, children, families? Are the majority of people we serve from a specific group who might benefit from a particular kind of intervention or treatment?

Goals for the intervention and/or treatment:

- Do we want to stabilize them after 1-3 sessions so they can be transitioned elsewhere? Do we want to offer long-term, intensive therapy? Do we want to provide brief treatment that can reduce suicidality but not necessarily address any underlying behavioral health issues? Do we want to address both suicidality and reduce symptoms of underlying behavioral health issues?

How we provide the intervention and/or treatment:

- Group, individual, in person, telehealth, telephone, email/text, all of the above?

Cost of training:

- What is our budget for this training? Is there a train-the-trainer option?

Sustainability of the training:

- Will we need to pay train each new person hired? Is there additional training needed for supervisors to assist staff? How expensive will it be to give refresher trainings, if needed?

Length of training:

- How do we interrupt service to provide important trainings to staff? Is there a productivity offset that needs to be accounted for? Do we need to stagger training across teams or departments to reduce impact on service?

Evidence base of the intervention and/or treatment:

- Is it evidence-based? Evidence-informed? Is there evidence that shows it works for our population? Was it studied for our treatment setting?

Related regulatory and/or accreditation requirements:

- Do the interventions/treatments we want to implement need to be approved by regulatory, funding, or accreditation bodies?

Fidelity monitoring:

- Does the training come with a fidelity checklist? How time-consuming will it be to check fidelity? How could we use our EHR to check fidelity?

Ability to adapt for different cultures:

- Can you identify the core components of the intervention/treatment and adapt it for the culture, population, or setting that you need it for? For example, can you adapt the language (e.g., for children, translate it into a different language), add or subtract things to be sensitive to the culture of the individuals receiving the intervention/treatment?

Fit to our organization’s culture, climate, and context:

- Will the intervention/treatment fit with the other interventions and treatments we use? Or is it very different from the interventions and treatments we normally use?

Planning Next Steps

There are several additional items to help plan next actions:

Getting Started with Zero Suicide

This one-page tool lists ten actions to take to start implementing Zero Suicide. Use this tool to get started on the path you will take to adopt this comprehensive suicide care approach.

Getting Further with Zero Suicide

This tool lists several actions you can take if you have been implementing Zero Suicide for a while and are not sure what to do next or need help taking your Zero Suicide work a little further.

Zero Suicide Organizational Self-Study

Every organization should complete the self-study as one of the first steps in adopting a Zero Suicide approach. While the self-study is available in the Lead section of the Zero Suicide online toolkit, it’s provided again here for your convenience.

Zero Suicide Work Plan Template

This form contains an expanded list of action steps to guide your implementation team in creating a full work plan to improve care and service delivery in each of the seven core Zero Suicide components.