Trinity Health Ann Arbor (THAA) is a community teaching hospital and tertiary care center that is part of the Trinity Health system in Michigan. Its staff of physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals have extensive training in specialty and tertiary care medical programs. It also provides behavioral health services.

Safety is one of THAA’s core values. THAA follows the Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals, which includes reducing the risk of suicide. In 2023, THAA started with the Suicide Care Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (SC CoIIN) to begin working toward a systemwide implementation of Zero Suicide practices.

Suicide Care Journey Stories

SC CoIIN Objective

The overall goal of the inpatient medical services units of THAA’s hospital was to provide a holistic approach to treatment by integrating their behavioral health and medical services. In joining the SC CoIIN, THAA sought to develop a clear pathway for screening, assessment, treatment, and discharge to help medical patients who were also at risk for suicide. THAA planned to start this work by implementing changes in one inpatient medical services unit.

According to Carlie Wilson, clinical nurse specialist, THAA’s objective was to look at “what systems, what processes we can put in place to really set up, not only our staff for success, but also our patients for appropriate care and success.”

Previous Experience with Suicide Care

At the beginning of their participation in the SC CoIIN, THAA gathered data to assess respectful, compassionate care. Surveys and data assessments conducted by their teams revealed that patients felt they were indeed receiving respectful and compassionate care. However, significant gaps were identified in the standard and structured suicide care for medical patients. These gaps included a lack of the following: comprehensive risk assessments for suicidality, formal evidence-based interventions, and a well-developed discharge planning process. Additionally, there was an absence of counseling on access to lethal means for patients identified at risk of suicide.

The social workers on the medical units provided services for patients with physical health problems, but the medical units had no licensed behavioral health clinician working with the psychiatrist to specifically address suicide risk. Comprehensive risk assessments and safety plans were not completed within the 24-hour goal for patients who screened positive for suicide risk. This delay occurred for two reasons—the psychiatrist was often unavailable due to other responsibilities, and some patients’ medical conditions affected their cognitive ability to participate in the risk assessment.

Suicide Care Interventions Implemented

The SC CoIIN team conducted a gap analysis that collected baseline data and reviewed workflow processes, policies, and procedures. From that analysis, THAA realized that to implement the changes they wanted, they needed a master’s level clinician (psychiatry consult liaison) who specialized in suicide care to work with the psychiatrist and support the medical teams. Midway through the SC CoIIN, they redirected their current behavioral health clinician to focus on risk assessments and management of patients who were at risk for suicide. She was responsible for safety planning, care transitions, and follow-up support after discharge.

To facilitate the integration of this clinician, THAA developed a process using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale1 for patients identified as having moderate to high risk for suicide. After implementing this process, they observed increased collaboration between the medical and behavioral health teams. This improvement led to more efficient care, which allowed for earlier intervention for patients who were at risk of suicide. It also led to collaborative implementation of evidence-based care structures.

THAA is continuing to improve their work on all of these processes. The clinician is currently developing discharge planning to help patients with their care transitions, including receiving follow-up care and caring contacts. THAA is also implementing QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer)2 training for staff to help increase the frequency and quality of screening and referral of patients for suicide-specific care.

Key Successes

A key success was bringing a clinician on staff to focus on providing suicide care. The clinician now conducts comprehensive risk assessments, counseling on access to lethal means, and brief treatment specific to suicide risk, such as Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS).3 This clinician also works with patients who are at moderate to high risk for suicide to develop a safety plan.

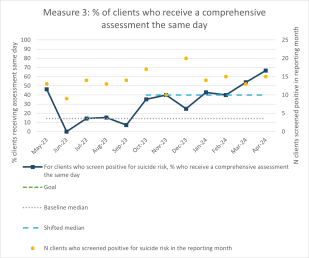

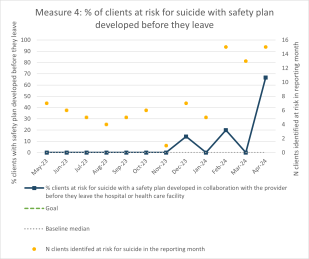

Adding this specialized clinician enabled THAA to improve the speed with which they assessed patients at risk of suicide. The number of patients with moderate to high risk for suicide who received a comprehensive risk assessment within 24 hours of being screened rose from 7% to 67% in about seven months. The assessment process has become a part of THAA’s suicide care pathway workflow, which helps with providing appropriate interventions and resources. The addition of this clinician has also helped to raise the rate of patients who develop a safety plan before discharge, from 0% in November 2023 to nearly 65% in April 2024.

“Thanks to the Suicide Care CoIIN, we have been able to successfully integrate behavioral health and medical services, which ensures safer suicide practices for our patients who are at risk,” said Melissa Tolstyka, director of behavioral health. “This comprehensive approach allows us to bring together both medical needs and mental health needs of our patients and really focuses on improved outcomes and a more effective response to suicide care.”

Lessons Learned

- Having a clinician dedicated to providing suicide care greatly increased and improved the services patients received.

- Clarifying to medical staff, especially the medical social workers, why change in the current processes was needed and obtaining their buy-in were critical to enabling change.

- It can take time to implement change to help patients with suicide risk in a health care system, especially when they are initially in the system for medical reasons.

Opportunities for Future Suicide Safer Care

Given THAA’s success in integrating a clinician into the medical services unit as part of the SC CoIIN, they are considering replicating this model in other medical services units. They also plan to continue streamlining the changes already made and are fully implementing the Zero Suicide model into THAA’s standard of care, while expanding this type of suicide care across the region and state.

“This [type of change in a health care system] isn’t something people can do quickly,” said Tolstyka. “This isn’t something like you’re on this path and you’re going to follow all these steps and everything’s going to be great. You’re following this path, and then you realize you have to go back to this first part of the process because it’s not working, or we might have not conveyed it the way we wanted to. So, give yourself grace.”

- 1

Posner, K. (2007). Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t52667-000

- 2

Quinnett, P. (2007). QPR Gatekeeper Training for Suicide Prevention The Model, Rationale and Theory. QPR Institute. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254002929_QPR_Gatekeeper_Training_for_Suicide_Prevention_The_Model_Rationale_and_Theory

- 3

Ryberg, W., Fosse, R., Zahl, P.H., Brorson, I., Møller, P., Landrø, N. I., & Jobes, D. (2016). Collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) for suicidal patients: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 17, 481. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1602-z