Mennonite Health System (MHS) is a large private nonprofit health system in Puerto Rico, operating six general hospitals and 11 emergency departments in the central and southern parts of the island. MHS also runs six outpatient mental health clinics and Centro De Salud Conductual Menonita (CIMA), a psychiatric hospital that offers inpatient care. With CIMA as one of only three Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs) on the island. MHS is a critical player in helping Puerto Ricans access mental health care.

Suicide Care Journey Stories

SC CoIIN Objective

In joining the Suicide Care Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (SC CoIIN), MHS sought to streamline their existing suicide prevention efforts, improve safety planning, and adopt universal screening for suicide. The team was motivated by a significant need: MHS serves municipalities with some of the highest rates of suicide on the island,1 and national research suggests that 83% of people who die by suicide are seen by a health care provider in the year before their death.2

“So that gave us a clue that we needed to start screening, we needed to start asking more questions, and we needed to start identifying these patients before they attempted to take their life,” said Clarrissa Cintron, quality and compliance director for MHS.

Previous Experience with Suicide Care

Prior to joining the SC CoIIN in 2023, MHS had already implemented a number of strategies designed to prevent suicide. All patients seen at emergency departments in MHS were screened for suicide. Clinical staff were also trained in suicide prevention and received in-depth training on protocols and tools to identify suicidal ideation. Safety planning procedures were also in place.

However, MHS struggled with consistency across these interventions and across their system. Hospitals used two different screening tools, making it difficult to compare data. Protocols for helping people move through the system’s suicide care pathway were not formally documented. Finally, clinicians did not use an evidence-based tool for developing safety plans, and the plans were often incomplete when patients were discharged. To support the system’s suicide care initiatives, MHS hired crisis managers at each of their emergency departments two months before the start of the SC CoIIN. These crisis managers supported the care transitions for people at risk of suicide.

Interventions Implemented

1. Screening Tools

The team’s first priority was to align suicide screening tools across the system. While CIMA was using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)3 screener, MHS’s emergency departments were using the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) screener. Using two screeners complicated systemwide data collection. It also led to some inefficiencies in delivering post-screening suicide risk assessments.

Creating consistency for both hospital staff and patients was an important part of establishing a clearer, more effective suicide care pathway. MHS decided to adopt the C-SSRS screener systemwide. They then brought in their crisis managers to administer a full assessment and referral, if needed, when any patient screened positive for suicide risk.

These changes helped to “restructure the pathway” and “made sure that the patient was being directed to the service needed,” said Cintron.

2. Safety Planning

MHS adopted other evidence-based tools to improve their suicide care pathway as well. After not previously using a formal safety planning tool, MHS chose to use the Stanley-Brown Safety Plan4 for people at risk of suicide. As part of this adoption MHS staff translated the tool, adapted it to be more culturally and linguistically relevant, and then trained staff on how to use it.

Completion of this safety plan is now required before patients who screen positive for suicide are discharged from inpatient care settings and partial hospitalization programs. If a patient at risk of suicide is seen in one of MHS’s emergency departments, a clinician is in charge of recommending whether or not a safety plan should be completed before discharge.

3. Professional Development

The MHS team also trained their social workers in the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS),5 Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM),6 and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP)7 interventions, increasing available evidence-based treatments for people at risk of suicide.

Key Successes

The creation of a formal, documented suicide care pathway has been the MHS team’s most significant success during their participation in the SC CoIIN.

“Before we joined the SC CoIIN, we already had processes in place for transferring patients [at risk of suicide],” said Cintron. “But now it’s more of a formal pathway. There’s more communication. I feel that we have filled in some of the gaps that existed previously.”

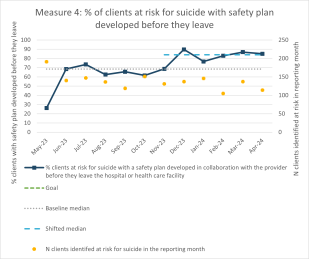

Safety planning has been one significant area of success. In May 2023, MHS reported that 26% of patients at risk of suicide had completed a safety plan before discharge. By April 2024, MHS had reached its goal of 85% of discharged patients with a completed safety plan.

The MHS team has also fostered more open and honest conversations about suicide. They felt this was important because of the stigma around suicide in Puerto Rico—even in healthcare settings.

To showcase their system’s goal of reducing deaths by suicide, the MHS team put the Zero Suicide logo into displays at hospitals and clinics. But many healthcare staff did not like the overt mentioning of suicide and mentioned their concerns to Humberto Cruz, clinical director of CIMA.

“They were not feeling okay about having that language on the displays,” said Cruz. “They asked, ‘What was the reason? Why are you putting the word suicide out there?’ Even though we are a high-rate catchment area for suicide, there’s still resistance about this topic.”

One way the team-initiated conversations about suicide was to share data about deaths by suicide in Puerto Rico, especially in areas served by MHS, during meetings and visits to hospitals and emergency departments. That data helped care providers understand the scope of the issue, and to see it as a threat to public health. It was particularly important for clinicians to understand that mentioning the word “suicide” to a person at risk of suicide does not put them at greater risk; in fact, it may reduce their risk.8 Before long, healthcare staff were opening up about their own lived experiences with suicide.

“We’re telling our employees and our organization, ‘This is what’s going on, and these are the numbers,’” said Cintron. “People are actually surprised. And then they will say, “I actually know someone who died by suicide. But I didn't know it was this big.’”

Lessons Learned

- Aligning existing screening, treatment, and discharge policies is critical to establishing a suicide care pathway.

- Strong leadership is critical to adopting and following through on systemwide change.

- Addressing the stigma surrounding suicide is a necessary part of improving care.

- Sharing data can help initiate conversations about suicide and suicide prevention.

- Improving suicide care requires staff buy-in, consistency of effort, and a focus on core goals.

Opportunities for Future Suicide Safer Care

MHS continues to build a culture of openness and hope with respect to suicide prevention. They continue to translate suicide prevention materials and interventions from English into Spanish, while also adjusting for cultural and linguistic appropriateness.

After participating in the SC CoIIN, MHS received a Zero Suicide grant from SAMHSA to continue the development of their suicide care pathway. Their future goals include adopting evidence-based treatments and expanding training for clinical and non-clinical employees. Finally, MHS plans to use evaluation and a continuous quality improvement model to guide their efforts.

- 1

Puerto Rico Department of Health (2023, December). Commission on Suicide Prevention. Slide 17. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/video/puerto-rico/Webinar-CDC-National-Center-for-Health-Statistics-15-December-2023.pdf

- 2

Ahmedani, B. K., Simon, G. E., Stewart, C., Beck, A., Waitzfelder, B. E., Rossom, R., Lynch, F., Owen-Smith, A., Hunkeler, E. M., Whiteside, U., Operskalski, B. H., Coffey, M. J., & Solberg, L. I. (2014). Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. Journal of general internal medicine, 29(6), 870–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3

- 3

Posner, K. (2007). Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t52667-000

- 4

Stanley, B., & Brown, G. (2012). Safety Planning Intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256–264.

- 5

Ryberg, W., Fosse, R., Zahl, P.H. et al. Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) for suicidal patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials17, 481 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1602-z

- 6

Sale, E., Hendricks, M., Weil, V., Miller, C., Perkins, S., & McCudden, S. (2018). Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM): An Evaluation of a Suicide Prevention Means Restriction Training Program for Mental Health Providers. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0190-z

- 7

Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy for the Prevention of Suicide Attempts: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2005;294(5):563–570. doi:10.1001/jama.294.5.563

- 8

Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, Fear NT. Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(16):3361-3363. doi:10.1017/S0033291714001299