The mission of the South Carolina Department of Mental Health (SCDMH) is to “support the recovery of people with mental illnesses” across the state. As South Carolina’s public mental health provider, SCDMH operates a network of accredited outpatient mental health centers and community clinics, as well as licensed hospitals. Residents who need inpatient care are treated at one of three facilities serving those age 18 and over: G. Werber Bryan Psychiatric Hospital (Adult and Forensic Divisions); Morris Village Alcohol and Drug Treatment Center; and Patrick B. Harris Psychiatric Hospital.

Suicide Care Journey Stories

SC CoIIN Objective

During the Suicide Care Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (SC CoIIN), SCDMH inpatient services focused on improving suicide care pathways across four individual sites: the three inpatient psychiatric sites with two hospitals, and the substance use disorder treatment facility. SCDMH aimed to test and implement changes in practice drawn from the Zero Suicide model to improve screening and assessment of suicide risk, enhance patient care and engagement, and support patients at time of discharge. Though these changes in practice only affected the groups of patients at the four sites, the lessons learned improved the suicide care pathway across SCDMH’s entire inpatient system of care.

Before joining the SC CoIIN, “We had the building blocks,” said Allyson Sipes, director of clinical initiatives for G. Werber Bryan Psychiatric Hospital. “But we recognized we had room for improvement. The SC CoIIN was a great opportunity to reevaluate where we were and where we needed to go.”

Previous Experience with Suicide Care

Since participating in Education Development Center’s Zero Suicide Academy in 2019, SCDMH has been committed to reforming its suicide care pathway in its inpatient services. However, adoption of Zero Suicide principles and approaches were slowed by various factors. First, the four sites participating in the SC CoIIN each served different patient populations and were at various stages of readiness for Zero Suicide implementation. Second, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 forced SCDMH to adjust how it delivered care for an extended period of time: providers had to balance quarantine and safety protocols with the mental health needs of patients, leaving less staff time to focus on Zero Suicide implementation.

By 2023, the inpatient system of care had made significant progress. The SCDMH’s Office of Suicide Prevention was conducting regular staff trainings on multiple evidence-based suicide prevention programs, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT),1 Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM),2 Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk (AMSR),3 and Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST).4 SCDMH was also using multiple tools from the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)5 to screen for and assess suicide risk. These tools were a core part of both inpatient and outpatient care and were featured prominently in the agency’s electronic health record system.

SCDMH had also developed its suicide care pathway, which included screening, assessment, treatment, safety planning, and expectations for caring contacts at patient discharge. However, the pathway was not implemented consistently across the four participating sites because of varying levels of staff knowledge and training.

Suicide Care Interventions Implemented

SCDMH implemented several important interventions during the SC CoIIN that strengthened its system’s suicide care pathway.

1. Screening and Assessment

SCDMH recognized a need to improve its electronic health records (EHR) system. Existing forms in the EHR did not explicitly detail the steps in the Zero Suicide care pathway, making it difficult for staff to track and deliver care to patients at risk of suicide.

With the guidance of someone with lived experience of suicide, SCDMH adopted multiple changes to help hospital staff more quickly identify a patient’s suicide risk. The EHR of a patient at risk for suicide now features the patient’s name in purple font, a specific icon in the banner, and a pop-up alert on all forms. SCDMH is also developing a script and training for clinicians to improve patients’ engagement during the C-SSRS screening and assessment. Once finished, this training will be a module in the agency’s e-learning system.

2. Patient Survey Assessing Care

SCDMH surveyed patients to assess their perception about whether care they received was respectful and compassionate. Initial feedback from patients led the CoIIN team to change the surveyor to a neutral person who is not involved in the patient’s direct care. Initially the survey was only conducted in one unit of the three hospitals, but SCDMH expanded the survey to gather information from two of the four sites serving patients on the suicide care pathway.

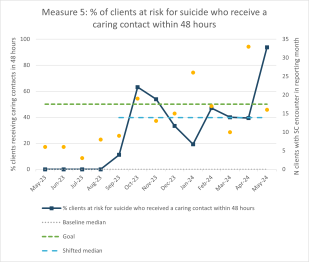

3. Caring Contacts

SCDMH reworked how facilities managed caring contacts, which are follow-up phone calls, texts, or postcards to people who have been recently discharged from inpatient care. Prior to 2023, data collection on caring contacts was not consistent, so SCDMH had little sense of how often they were conducted. During the SC CoIIN, SCDMH revised its EHR to allow for more consistent data collection about caring contacts. The CoIIN team also created a set of protocols for contacting discharged patients. Now, SCDMH tracks the percentage of patients on the pathway who receive a safety call within 24 hours of discharge and who are sent a caring contact card within 72 hours of discharge.

Key Successes

Participating in the SC CoIIN provided SCDMH staff the opportunity to identify and assess variations in suicide safe care processes across four sites. This process helped team members realize that each site had a unique context and required adaptations to the suicide care pathway.

“We were able to look at the individual, unique workflows for our sites and better understand how to revise the pathway so that their discrete needs were supported,” said Sipes. “As soon as they got the chance to learn some of the elements and drivers we were working on, it was clear that they all had the same intention, which was to implement Zero Suicide.”

SCDMH also took the important step of adding a patient affairs coordinator who has lived experience with suicide to its team. This person helped team members better understand the importance of nonjudgmental language throughout the suicide care process, from conversations with patients to the terms used within the EHR. Having this person on the team “challenged us to really work differently, think differently, and understand that we must have lived experience at the table,” said Sipes.

Lesson Learned

- Embedding suicide safer care in the EHR can support practitioners’ adherence to the suicide care pathway.

- Brief, localized tests of change lead to wider improvements in delivering suicide safer care.

- Communication and buy-in across different sites, roles, and responsibilities are essential to making changes.

- It is critical to have people with lived experience on the suicide care planning team.

- Understanding and communicating data provides opportunities to guide change and measure progress.

Opportunities for Future Suicide Safer Care

In the coming months, SCDMH inpatient services plans to continue its journey towards Zero Suicide. Specifically, it plans to expand clinician training around screening and assessment tools, treatment and safety planning, and caring contacts. It also plans to embed lethal means counseling within its EHR. Finally, SCDMH will continue to work with hospital leaders to prioritize the consistent adoption of the suicide care pathway.

“Through the SC CoIIN, we were able to bring in more interdisciplinary leaders and champions, and really broaden our understanding and knowledge of suicide-specific care,” said Sipes. The result is that SCDMH is “in a good place to move forward” with more effective, consistent communication across its care system.

- 1

Linehan, M. M., Armstrong, H. E., Suarez, A., Allmon, D., & Heard, H. L. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(12), 1060–1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003

- 2

Sale, E., Hendricks, M., Weil, V., Miller, C., Perkins, S., & McCudden, S. (2018). Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM): An evaluation of a suicide prevention means restriction training program for mental health providers. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0190-z

- 3

Education Development Center. (2019). Assessing and Managing Suicide Risk: Core Competencies for Health and Behavioral Health Professionals Working in Inpatient Settings.

- 4

Rodgers, P. (2010). Review of the Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training Program: ASIST Rationale, Evaluation, Results and Directions for Future Research. LivingWorks Education Inc. https://legacy.livingworks.net/dmsdocument/274

- 5

Posner, K. (2007). Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t52667-000