Best and Promising Practices for the Implementation of Zero Suicide in Indian Country

Zero Suicide is a highly effective framework for the creation of suicide-safer care that can be adapted to a range of health and behavioral healthcare systems. Use this adaptation as a supplement to the Zero Suicide Toolkit.

Zero Suicide in Indian Country

Zero Suicide in Indian Country

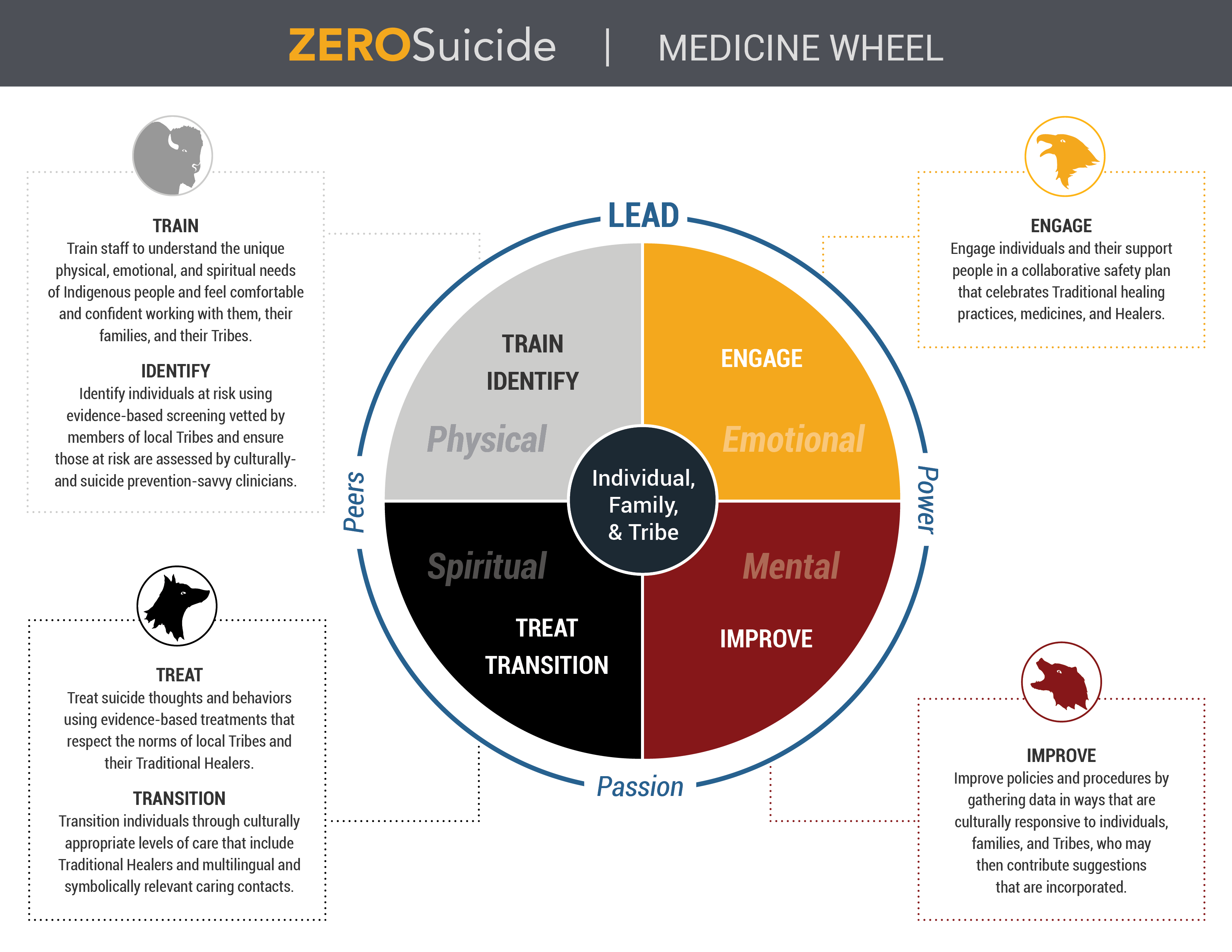

Zero Suicide is a framework to support suicide-safer care in health and behavioral health care systems. In the past ten years, multiple rigorous studies have shown that Zero Suicide is effective in reducing suicide deaths across many health systems. Still, when health and behavioral healthcare systems in Indian Country have attempted to employ the framework, there are often challenges related to culture, language, or concepts of what healing and wellness may mean to the Tribe or to the community. There have also been differences in resources and views of standardized measurement and data gathering. Adding to the challenges of implementing Zero Suicide as a framework in Indian Country is a history of shared adverse experiences across multiple generations that have impacted the health and well-being of Indigenous people.

“Resilience is part of our DNA. I have hope and faith that our Ancestors are standing beside us as we wrap our collective arms around our babies to end their loss in our Tribes, villages, and communities. I have faith that the field will recognize that evidence-based practices are fine for some, but not for all. And while our ways may not be studied and written up in medical journals, they have worked for thousands of years.”

— Sadé’ Heart of the Hawk Ali, Mi’kmaq First Nation from the Sturgeon Clan, adaptor of the Zero Suicide Toolkit for Indian Country

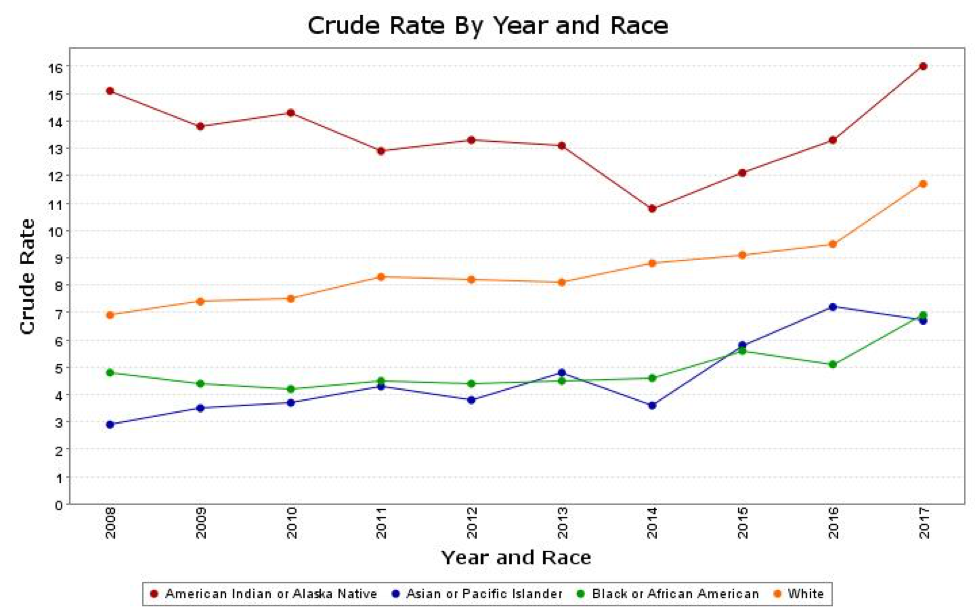

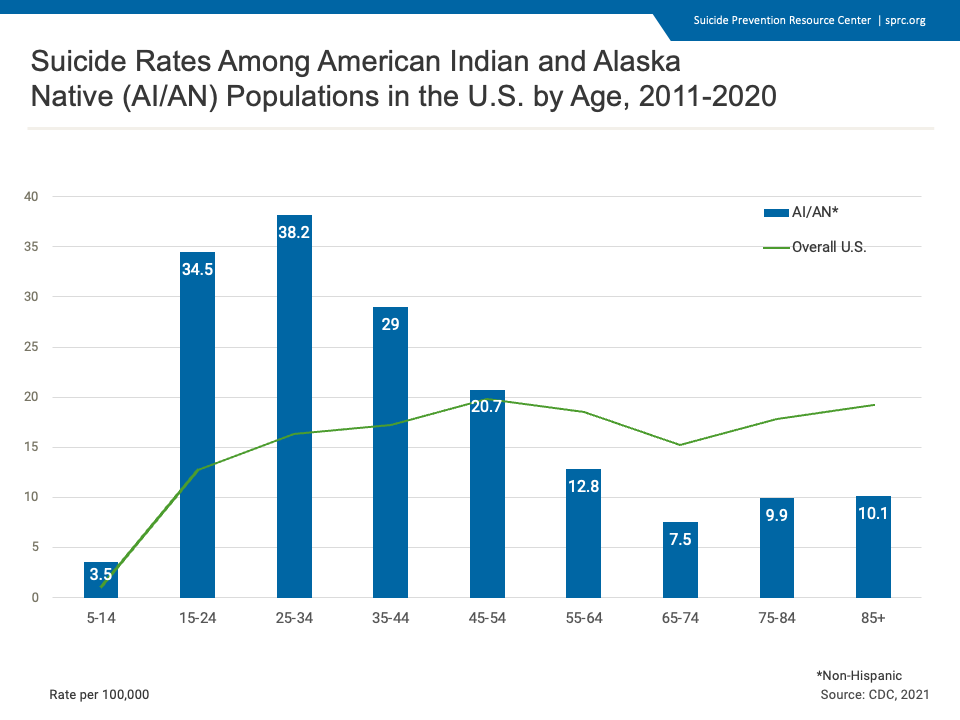

Suicide death rates for Indigenous people are greater than that of the general population. Indigenous children are more likely to end their lives by suicide than any other group of young people. However, in many Tribes across Indian Country, suicide is a “never event.” Indigenous people have the highest rates of sobriety of any other cultural group and, as Indigenous people age and reach 60 years or older, the suicide rate drops significantly compared to that of any other groups.1

The evidence-based practices that are promoted in the Zero Suicide framework have not been validated on Indigenous people. Therefore, a combination of the western ways and concepts outlined in the Zero Suicide framework, and the use of Traditional Healers and medicines may prove more effective when working with Indigenous people and communities, especially if the Tribe or community is more traditional in their ways.

Currently, concerns about the appropriateness of evidence-based practices include inadequate or lack of cultural variables in research samples, no examination of the impacts of culture on outcomes, no adequate consideration for mental health and substance use challenges that occur together, and lack of consideration for context and environment.

Many of those involved in the development of EBPs believe that better outcomes are best achieved through application of scientific methodologies and that “science” surpasses culture. … Those who are proponents of cultural relevance believe that science is important, but that culture and other social factors, such as social role, gender, ethnicity, and place, cannot be ignored.

— M.K. Isaacs

Issacs and colleagues believe that, in order for better outcomes to be achieved through the use of evidence-based practices, each individual’s values, beliefs, identity, behaviors, and social norms must be considered..2 Applying this concept to Tribal communities, there is no such thing as “Native Culture.” Rather, there are thousands of unique cultures. When we focus our attention on the Tribe itself, its healing ways, its leadership (i.e., Chief, Governor, President, and/or Chairperson, as well as the Tribal Council and its Youth and Elders Councils), Zero Suicide may be implemented effectively and appropriately.

This toolkit adaptation contains recommendations for the implementation of Zero Suicide in Indian Country, forms and tools others have used in their own implementation, and videos featuring a variety of Indigenous health systems (IHS and Tribal) that have committed to the implementation and indigenization of the Zero Suicide framework for their communities. We offer two in-depth views into very different health systems—one Tribal and one IHS—that are implementing Zero Suicide.

This is a companion toolkit to the original Zero Suicide Toolkit. The toolkit on the Zero Suicide website details each of the seven elements that make up the Zero Suicide framework for health and behavioral health care systems and should form the basis for anyone starting to learn about Zero Suicide. This companion toolkit serves as a specialization step for health systems that are looking for guidance on how to implement the Zero Suicide framework.

Best and Promising Practices for the Implementation of Zero Suicide in Health and Behavioral Health Care Systems in Indian Country gives recommendations on how the Zero Suicide framework can be used in Indigenous-serving systems that are Tribally owned and managed as well as those managed by Indian Health Services.

The following resources are available as addendums:

- Zero Suicide Keys for Sustainability for Health and Behavioral Health Care Programs in Indian Country

- Is Your Tribal or IHS-Led System Ready to Implement Zero Suicide?

- Is Your Tribal or IHS-Led System Not Quite Ready to Implement Zero Suicide?

- Getting Started with Zero Suicide in Indian Country

A Word About Language

Throughout this toolkit, we have removed labels as much as possible. People are not suicidal. They are experiencing suicidal thoughts and possibly behaviors. People are experiencing challenges with, in recovery from, or experiencing symptoms of…rather than actually being those challenges. To identify people by their challenges, no matter what they may be (substance use, mental health challenges, suicidality, etc.), takes away their humanity, reducing them to the challenge. Therefore, the use of the terms patient, client, consumer, etc. will also not be used. Rather, the terms people/family/families receiving services, people coming for services, individuals, and people with whom we partner on their roads to recovery will be used. Just because a term has always been used, does not make it right, affirming, or accepted by those to whom it is directed.

- 1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2017 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December 2018. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2017, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Jun 29, 2019 12:20:42 PM

- 2Isaacs, M.R., Huang, L.N., Hernandez, M. & Echo-Hawk, H. (December, 2005). The Road to Evidence: The Intersection of Evidence-Based Practices and Cultural Competence in Children’s Mental Health. Paper prepared for the National Alliance of Multiethnic Behavioral Health Associations, Washington D.C.

LEAD Defined

Lead a system-wide culture change committed to reducing suicide deaths.

Two leadership drives are the keys to the dramatic reductions in suicide deaths achieved by Zero Suicide organizations. The first is leadership mobilizing staff to believe that suicide can be prevented. The second is an unwavering focus maintaining that zero suicides is the goal. Leadership must both convince staff to see and believe that suicide can be prevented and provide tangible supports in a safe and blame-free environment—what is known as a just culture.

LEAD Indigenized

Whereas the definition above begins with the leadership of a health or behavioral health care system, leadership and the element of LEAD can take on very culturally-specific meanings when the terms are used in Indian Country. Leaders may be the Tribal Chief, Governor, Chairperson, or President (elected or Traditional). They may be the Tribal Council (elected) and, many times, the Elders Council (non-elected, ceremonial positions of honor based on age, knowledge, and roles within the Tribe or community). Some Tribes include youth as part of their leadership structure as well as Traditional Healers.

In Tribally-owned systems, the layers of accountability are often multiple and take time, patience, and perseverance to maneuver and navigate. Leadership in a Tribally-owned system does not begin at the health or behavioral health care level. It begins on the ground at the community level and often with Tribal resolutions endorsed or written by the Chief/President/Governor/Chairperson, the Tribal Council and the Elders. Sample Tribal proclamations related to suicide prevention in a Tribe can be found here:

- White Mountain Apache Tribe Resolution No. 09-2006-333

- White Mountain Apache Tribe Resolution No. 11-2009-365

- White Mountain Apache Tribe Resolution No. 05-2012-4

Attention is paid to cultural protocols and Traditional ways specific to the Tribe or Tribal community when approaching Tribal system leaders for support for a Zero Suicide implementation. The Chief/President/Governor/Chairperson, the Tribal Council, the Elders, youth, and Traditional Healers (if they are part of the Tribe’s culture) are invited to become members of the implementation/leadership team in an effort to maintain their support and guidance. Any IHS Service Unit providing any type of health or behavioral health care services to the Tribally-owned system should also have membership on this team.

This inclusion of the Tribe’s governing systems, their youth, their Traditional Healers and their Elders on leadership and implementation teams creates unique opportunities when ensuring that the process begins as recommended in the Zero Suicide framework with an Organizational Self-Study. An Organizational Self-Study allows a system to take a snapshot of where its gaps are at a point in time and helps the leadership/implementation team to plan for the future. At this time, the Organizational Self-Study is very systems-based and there are not many (if any at all) opportunities for those outside of the system itself to “see themselves” in it. With some modification by the Tribal or IHS-led system, the Organizational Self-Study could be made more resonant with inclusion of Tribal governing systems, including Elders, Traditional Healers, and youth, helping to ensure full participation of the community and its leaders. An example of some language to use when using the Organizational Self-study is found below.

In Indian Health Service (IHS) facilities, where health care is delivered primarily by IHS, the organizational structure may look somewhat different. The IHS, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services, is responsible for providing federal health services to Indigenous people. IHS is headquartered in Rockville, MD, with twelve area offices across the country and operates many service units with federally-owned hospitals and health centers under the jurisdiction of each of the twelve geographic areas.

Whether the health care system seeking to implement Zero Suicide is Tribally-owned or is one led by IHS, it is always recommended to ensure that the Tribal community (or communities) in which the health care system is located is/are part of the Zero Suicide leadership/implementation team. For IHS-led health care systems, the IHS service unit responsible for the system, in cooperation with IHS Headquarters and the corresponding Area Office, will facilitate this.

A note about Indigenous people with lived experience and how to engage us:

For a great many years, and although in Indigenous groups there are many incidences of attempted suicide and loss of loved ones to suicide, as a result of shame, few of us talked about it or admitted that we had survived either attempts or loss. As a result of the movement in the field of Suicidology, away from shame and toward the light of empowerment, many more of us Indigenous people are claiming the position of Survivor. Several Tribal people nationally are becoming voices for survivorship and are sharing their stories of resilience and triumph in the face of adversity. As much as possible, attempt to engage people who may have been seen or whose loved one(s) may have been seen in your health care systems. We are powerful tools for engaging others (both people needing services and providers who may not see the need for suicide-safer care) and for “putting a face” on both the challenge and the positive outcome. We are the role models for survival who are testaments to the resilience of Indigenous people and to the affirming, suicide-safer care we may have received in your system.

— Tribal Elder, Mi’kmaq First Nation, suicide attempt survivor

What does it mean to engage Tribal people with lived experience of suicide attempt or loss of a loved one?

For many Tribal people, there is a great deal of shame around either admitting that you have lost someone to suicide or that you have attempted to end your own life. For this reason, it is important to create what the Zero Suicide framework calls a just culture in the health or behavioral health care systems operating in Indian Country and with Tribal people.

For the framework in general, creating a just culture means that the entire system takes the responsibility for safer suicide care and that if a loss does happen, there is no blame. Rather, there is a coordinated response that includes an examination of factors related to the loss and a plan to close gaps in order to mitigate occurrences in the future. Safe suicide care is viewed by systems with a just culture as understanding that the safety of people and families coming for services is just as important as taking vital signs at each visit. In fact, the screening for suicidal thoughts or behaviors is viewed as just another vital sign and as standard procedure when working with someone to ensure their health and wellness. In a system with a just culture, suicidality becomes another routinized health care challenge for which they check, like diabetes or high blood pressure, taking the mystique out of it. When this mindset is in place and part of the culture, people who have lost a loved one to suicide or those who have attempted to end their own lives are more likely to be open about that because challenges with suicidal thoughts or behaviors are recognized as just another health care challenge to be addressed in a comprehensive manner.

For Indigenous-serving systems, this also means first developing trust with the community, listening without judgment to how they articulate loss of life to suicide, and asking for guidance when crafting interventions, developing protocols, and creating policies and procedures. Often, once trust is earned, this creates fertile ground for the sharing of stories and experiences. People want to be assured that what they share is not going to be used against them, either to shame them or to make them feel as if they are incompetent or weak.

A toolkit for engaging Indigenous people with lived experience is located here: We are not the problem, we are part of the solution: Indigenous Lived Experience Project Report. Another good resource used by folks throughout the country, especially Indian County, is Community Readiness. It assesses the perceptions of the community to address prevention and treatment of suicide. Native Connections (SAMHSA) has required it for launching Suicide Prevention in Native Communities. The manual for Community Readiness is available as a free download request. Resources on community readiness to engage in system change are located here: Walking Softly to Heal: The Importance of Community Readiness.

LEAD: Key Considerations for Indian Country

- Research and understand the cultural context of the community targeted by your program;

- Ensure that your team includes a diverse representation of members from your target population throughout the planning, implementation, and evaluation processes;

- Ask for assistance with approaching the leadership of the Tribes on whose lands the health/behavioral health care system is located. If you are unsure about the most respectful way in which to do this, ask for assistance from those Indigenous people who may work in the system;

- Consider the creation of a Tribal or Cultural Liaison position on staff who will not only be part of the leadership/implementation team but will also be an important link back to the Tribe;

- Tailor information and resources to respectfully address your target population’s values, beliefs, culture, and language. Use alternative formats (e.g., audiotape, large print, storytelling) whenever appropriate;

- Create an open dialogue with group members to promote cultural considerations being honored and communicated, such as preferences regarding personal space, geography, familiarity, and terminology (i.e., words that should be used or avoided).1

Organizational Self-Study Addendum

The Organizational Self-Study is designed to allow you to assess what components of the comprehensive Zero Suicide approach your organization currently has in place. The Organizational Self-Study Addendum for Tribal or IHS-led Health Systems represents both the background/rationale and questions that may be amended to be resonant with the inclusion of Tribal communities in the process of implementing Zero Suicide in a Tribal or IHS-led health system.

- 1Culturally Competent Approaches. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.sprc.org/keys-success/culturally-competent

TRAIN Defined

Defined Train a competent, confident, and caring workforce.

Employees are assessed for the beliefs, training, and skills needed to care for individuals at risk for suicide. All employees, clinical and non-clinical, receive suicide prevention training appropriate to their role.

TRAIN Indigenized

All training is not created equal and training to create culturally-resonant, safer suicide care in Indian Country is no exception. Training that was created for other groups should be carefully reviewed to ensure that the concepts, tone, and language used are appropriate for the community being served. Great care must be taken when working with Tribal communities that screening and assessment tools, as well as other documents, use language that is affirming and healing to promote acceptance of care. Additionally, great care must be exercised in efforts not to retraumatize an individual and/or family who comes for services.

The entire system should have suicide-specific training of a type appropriate to their roles to ensure that they understand that people who are experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors may enter it anywhere in the health care system, and not only in behavioral health. Training for maintenance staff, front desk/receptionist, or dietary staff will look very different than that of clinical staff responsible for delivering therapeutic care to individuals and families.

Many sites in Native communities who are seeking to provide suicide-safer care through the use of the Zero Suicide framework are using QPR or ASIST for their non-clinical staff and either the ASQ or the PHQ with question 9 for screening for their clinical staff. IHS is presently piloting the use of the ASQ at select service units.

As with other systems in the US, the hiring of people, even those with advanced degrees, does not guarantee knowledge on how to work effectively with people who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors. In fact, except for a few very progressive institutions of higher learning, students may graduate with advance degrees never having had a course, a workshop, or even a lecture or symposium on suicide prevention or the provision of suicide-safer care. And, even if clinicians are trained on the provision of suicide-safer care or the Zero Suicide framework, there is no guarantee that they are able to provide this care in ways that are culturally-affirming for the people being served.

Great care should be exercised when choosing training for safer suicide care in Indian Country. For many Tribes/Tribal communities the discussion of suicide or death is taboo and the preference is for dialogue that promotes the sacred nature of life. See the section on the reworking of screening and assessment tools to be culturally resonant which follows. Consulting with the Tribal leaders, Traditional Healers, Elders, and youth will aid the system with ensuring that the tools used reflect the culture of the community and how loss of life by suicide is articulated.

The Zero Suicide Workforce Survey is a tool for taking the temperature of a health system’s workforce. It evaluates how well-prepared staff perceive themselves to be to work with people who may be experiencing challenges with suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Confidential, and available online or in a downloadable PDF, it is an effective tool to use in planning a training program for all staff in the health/behavioral health care system regardless of their role.

Notes:

- Attrition is a challenge in any system. Best and promising practices suggest that training is part of an HR onboarding process and that yearly “boosters” of training appropriate to roles are written into performance improvement plans for all staff.

- With a few small additions related to comfort levels when working specifically with Tribal people who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors, the Workforce Survey could be (re)designed for culturally-relevant use with Indigenous-serving systems. An example of ways in which to amend the Workforce Survey for use with Indigenous-serving health/behavioral health care systems is shown at the end of this section.

- Through the use of satisfaction surveys from Tribal people receiving services, individual and group supervision and self-reports on the Workforce Survey, staff should be assessed for their cultural knowledge and skill when working with the Tribal population in which the health/behavioral health care system operates and training on the community should be provided regularly to all staff. Regular in-service presentations, attendance at community gatherings, health fairs, and other Tribal-related functions may help with the acquisition of knowledge necessary to provide care that is culturally-resonant with the people being served.

- Badge cards may be helpful tools for every staff member. These cards can contain what to look for, who to call, and how to respond to someone who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors, even if the staff member’s duty is not clinical in nature.

TRAIN: Key considerations for Indian Country

- Part of the onboarding of all new staff should include suicide-safer care training that is appropriate for the position; gatekeeper training for non-clinical staff and screening, assessment, safety planning, and treatment interventions training for clinical staff.

- Badge cards with steps to take when encountering an individual who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behavior are available for and worn by all staff, regardless of position. These are especially helpful for those who may not be clinical in knowing what to do when they meet a person receiving services who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

- Do yearly inquiries into staff comfort around providing caring, confident and competent suicide-safer care for Indigenous people using the Workforce Survey. Update this following any major training effort and assure staff that these surveys are anonymous.

- Ensure that all staff understand the culture or cultures of the Indigenous people and their families receiving care in the health/behavioral health care settings in which they work. There is no such thing as “one size fits all,” especially when working with and in Indigenous communities. Staff must be aware that not everything is written in books and that many of the healing ways of Indigenous communities, while not researched and documented, are thousands of years old. Cultural humility when working with Indigenous people is an art that must be a cornerstone of Zero Suicide implementation and its sustainability post-funding in order for it to be successful.

- Encourage cultural sharing between the Tribe or Tribes and the health/behavioral health care setting. Participation in health fairs, open houses/community appreciation events at the hospital/health care setting, gatherings, homecomings, Powwows, etc., bridge the gap between health care and the community.

Recognize that there are often challenges with hiring staff in health systems in Indian Country that are more rural and remote, leading to either high rates of attrition or being understaffed in general. It is important for the health/behavioral health care systems operating in these areas to establish community connections with the supports found indigenously there. These supports include Traditional Healers, Elder Circles, youth-serving organizations, crisis response teams, first responders, schools, spiritual/religious organizations, and other health and behavioral health care providers. Providing gatekeeper training such as ASIST and QPR to these supports will aid in early identification of and intervention for people who may be at risk.

- Some suggestions for ensuring that gatekeeper training is resonant with the community in which the system is located follows: Guidance for Culturally Adapting Gatekeeper Trainings.

- A template for reviewing your Workforce Survey results can be found here: Reviewing the Workforce Survey Results.

- A comprehensive list of suggested training, the description of each, and the staff levels for which each is designed is contained here: Suicide Care Training Options.

Workforce Survey

The Zero Suicide Workforce Survey contains skills and knowledge-based queries for providing suicide-safer care based on the Zero Suicide framework for health and behavioral health care settings. Previously, we provided the Addendum to the Workforce Survey Related to Providing Culturally Appropriate Safer Care in Tribal and IHS-Led Systems to present suggestions for Indigenizing the Workforce Survey for use in systems serving primarily Indigenous and Tribal people.

Building on this addendum, we created the full Zero Suicide Workforce Survey: Zero Suicide Workforce Survey Questions: Indigenous (American Indian/Alaska Native) Version.

IDENTIFY Defined

Identify individuals with suicide risk via comprehensive screening and assessment.

Every individual coming for services is screened for suicidal thoughts and behaviors when health and behavioral health care organizations are committed to safer suicide care. All persons receiving care are screened for suicidal thoughts and behaviors at intake. Whenever an individual screens positive for suicide risk, a full risk formulation is completed for them.

IDENTIFY Indigenized

Expert suicideologists recommend a suicide risk screen at every visit, regardless of where the individual shows up in the health care system. Screening for suicide risk should be viewed as just another vital sign that needs to be collected for good medical care, just like temperatures, pulses and blood pressure checks. For systems that have an EHR, screening and assessment tools embedded into it facilitate the sharing of important clinical information such as suicide risk with other areas of the hospital or clinic and helps to minimize duplication if the person is seen in one or more areas of the health system within the same day.

While the Zero Suicide framework does not promote the use of one screening or assessment tool over another, it highly recommends use of evidence-based assessment and screening tools. Once any evidence-based tools have been selected, they should also undergo a thorough examination by the leadership/implementation team to ensure cultural relevance and appropriate language, based on the Tribal community in which they are being used. As previously discussed, the term evidence-based often has little resonance with Indigenous people as very little of that evidence, especially around tools for screening and assessment of suicide risk or treatment models, was validated in or on Tribal populations. Therefore, in the IDENTIFY element, often the task that is required is to take existing tools that were validated in other populations and rework them to make them relevant to Tribal people without compromising their validity. Often, as in the example below, that relevance is achieved by simply ensuring that the language is not offensive or disturbing to the Tribe and that it reflects the ways in which the Tribe articulates loss of life by suicide.

Authors of screening tools, assessments and other tools used in the Zero Suicide framework are often amenable to the adaptation of their instruments to align with the needs of the community being served and there are many examples of this type of cultural adaptation. It is possible that this alignment may be accomplished without compromising the validity of the instrument.

One example of a cultural adaptation of an evidence-based tool is the ASQ, presently undergoing pilot testing in several IHS Service Units. At the Chinle Indian Health Service in the Diné Nation in Arizona, studies are underway to validate the ASQ with language changes that include replacing “dead” with “not alive” and “kill yourself” with “take your own life.” The Chief of Primary Care, Dr. Nurit Harari, has conducted focus groups, not only with the Diné medical staff at the Service Unit, but also with Elders, Traditional Healers, and youth in the Tribal community being served by the Service Unit, to ensure the cultural adaptation is done appropriately. Two important things from the youth came out of these conversations: 1) the youth did not want others in the room while they are being screened and; 2) even if youth did not screen positive for suicidal thoughts or behaviors, they wanted a resource card with relevant numbers, websites, etc.1

Great care should be exercised when working with Indigenous people who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors to ensure that they feel supported and safe. A respectful, working knowledge of the culture or cultures of the Tribes where services are located should be a pre-requisite for those doing suicide-safer care in Indian Country. This ensures that the tools used are appropriate for the people receiving them and reduces the opportunity to re-traumatize individuals and families who are already stressed and in pain.

Though most all who work in the suicide prevention field would agree that those at risk must be helped to feel safe and supported, it is important to keep in mind that what it takes to feel “safe” is to a large extent both individual (informing the trauma-informed movement) and cultural. So, the usual things health professionals do to help non-Native communities to feel safe may not be culturally resonant or relevant for Native communities. It is not enough to simply adapt tools and instruments and language within health systems to be Native-specific, but the interactions, tone, goals, and approaches used during health system encounters must also be Native-resonant.

Some guidelines on best practices for assessing people who may be at risk for harming themselves is found here: Solutions That Work: What the Evidence and Our People Tell Us. Please note that although this guide was created in Australia, the Indigenous people there have many of the same challenges as those of Turtle Island (North America) in that they are still struggling with the impacts of intergenerational, historical and modern-day trauma, many Aboriginal communities face the same type of food deserts and lack of resources, and loss of their people by suicide is triple that of the national average. However, just like their Relatives on Turtle Island, there is a great deal of resilience, pride, and hope for healing.

IDENTIFY: Key considerations for Indian Country

- Keep in mind that health/behavioral health staff implementing Zero Suicide may come from the Tribal community or communities served. Many of these Tribes have taboos around talking about death, especially death by suicide. Research this, and if this is the case, encourage Indigenous staff to talk about life promotion instead of suicide prevention or death by suicide. Consult with the Elders of the Tribe for suggestions of the most appropriate language to use.

- IHS is promoting the use of the ASQ for screening in their Service Units. Some of the Tribal sites have been working with the authors of this tool to indigenize it without tampering with its integrity. They are finding it more culturally resonant and much easier to use with Indigenous people. However, choosing evidence-based screening and assessment tools as an implementation team with representation from the Tribe ensures buy-in and a sense of collaboration and ownership of the process.

- There is no substitute for cultural humility when working with Indigenous people, especially when working with screening tools and assessments that were not validated on them. This knowledge assists the suicide-savvy, culturally-savvy clinician with asking the questions in ways that will elicit answers while maintaining the respect and dignity of the individual who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors and maintaining the integrity of the tool.

- Realize that it may have taken a good deal of strength for someone to come in asking for help. Honor and support that by making a point to acknowledge this with the individual and by using the tone and ways in which suicidal thoughts and behaviors are articulated within the Tribe.

- Always ask about the use of traditional forms of healing in ways that show openness and acceptance of other ways of regaining health and balance. Don’t ask, “You don’t use Traditional Healers, do you?” If people or families coming for services do use Tradition Healers or medicines for wellness, ensure that the health/behavioral health care system has ways for them to contact those Healers immediately. Have telephone numbers on hand. Some systems have specialized clinics located right in the hospital. Some have Traditional Healers or Cultural Liaisons on staff and readily available.

- Some Tribal systems use the free Native American Acculturation Scale located here in Tip 59 from SAMHSA, which asks 20 questions to ascertain an individual’s level of involvement with their Tribal culture as part of their intake process or as they screen the individual for suicide risk. Use this knowledge to assist the individual with accessing the care that will be most healing for them.

- Every single door in the health or behavioral health care system, no matter where it is, should be open and able to screen and assess individuals for risk of suicide.

- 1Harari, N. (2019, August 23). Personal interview.

ENGAGE Defined

Engage all individuals at-risk of suicide using a suicide care management plan.

When an organization makes a commitment to Zero Suicide, every individual who is identified as being at risk for suicide is closely followed. They are engaged and re-engaged at every encounter no matter the reason for the visit. All individuals identified to be at risk of suicide are engaged in a Suicide Care Management Plan. The person’s status on a suicide care management plan is monitored and documented in an electronic health record (EHR). Organizations that have reported the most success providing people with a pathway to care use the electronic health record (EHR) to flag them as at risk for suicide

All individuals identified as being at risk for suicide in primary care practices and clinics, hospitals and emergency departments, behavioral health organizations, and crisis services should have a safety plan. Every safety plan should address reduction of access to any lethal means that are available to the person who may be at risk. Limiting access to medications and chemicals and removing or locking up firearms and other weapons are important actions to keep people safe.

Below is a video of Dr. Shannon Dial of the Chickasaw Nation Tribal Health discussing how implementation of Zero Suicide in their Emergency Department has improved suicide care for patients.

ENGAGE Indigenized

The nature of health care delivery in Indian Country, the sometimes antiquated methods of documenting that health care, and issues such as lack of communication between the various clinics, hospitals, and providers—some of whom are many miles apart from each other—creates challenges when engaging the individual experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

Engagement of individuals who have been deemed to be at risk for suicide through a screening and a comprehensive risk assessment by a clinician, doctor, physician’s assistant (PA), or nurse who is skilled at the administration of them, is critical to the successful reduction of risk.

Three major elements are part of the Zero Suicide framework’s element of ENGAGE.

Creation of a clinical care pathway or care management plan

Ideally, there are policies and procedures around the safe, most effective care for people experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors and coming for services in the health/behavioral health care system. Policies and procedures detail the course of action when individuals may be at risk. This course of action can be compared to that of any other medical or behavioral health challenge for which there are defined courses of action taken to mitigate the challenge.

For example, if a person appears in an emergency department with chest pains, medical staff know automatically that: 1) they are triaged immediately; 2) they are taken into a treatment room where their blood pressure is checked, an EKG is completed, and their blood is drawn for cardiac enzymes; and 3) if these screens are inconclusive, it is more than likely that they will get admitted for further observation and more cardiac testing. This is called a clinical care pathway, or care management plan; a systematic set of actions and interventions in response to a medical or behavioral health emergency.

The same holds true for those who may be a risk for suicide. The following diagram represents a model for that pathway. Pathways are created based on services existing in the health/behavioral health care system as well as those found in the community. The pathway is housed in the electronic health record so that all staff who have access to that particular record know that the individual is on it. Ideally, there is a banner or some other type of notification or color-code that alerts everyone with access to their medical record that the individual is at risk. All clinical staff are trained in the policies and procedures for putting an individual who may be at risk onto the pathway as well as to how and when to take them off.

When an individual is placed on this clinical care pathway, they are educated around both what it means to be on it and what they can expect to happen. They know exactly why they were placed on it and what needs to change in order for them to be removed from it. Often, this is accomplished through both verbal communication and through a one-page information sheet given to the individual and/or family members to supplement the conversation. Ensure that the information sheet is available in the languages of the Tribes within whose lands the health/behavioral health system is providing care. Many of the Tribes speak only their Ancestral languages and for others English is a second language and they may not read it well enough to understand the importance of what the sheet contains.

Figure 2. Model clinical care pathway

Creation of a safety plan

One of the most powerful therapeutic interventions, especially for Indigenous people, is safety or crisis planning. Research on this intervention has shown it to be efficacious for those experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Training to assist an individual with the creation of their safety plan is free or low cost and an advanced degree is unnecessary. It is resonant with Indigenous ways of healing because the plan is personal to the individual. The staff person can provide resources and cue the individual to identify helpful wellness strategies, people, and systems -- their personal medicine. Training is a key to making sure a safety plan intervention is successful. A guide for building these skills is located here: Safety Planning Guide: A Quick Guide for Clinicians. A sample safety plan template that can be accessed here: Patient Safety Plan Template.

While Zero Suicide Institute does not endorse one type of safety or crisis plan over another, the Stanley-Brown Safety Plan is comprehensive, easy to complete and easily adaptable to Indian Country and Tribal people. This safety plan is not clinician-driven but personalized to the individual’s view of how to achieve balance and wellness and how to stay safe if or when suicidal feelings arise.

The support of family or other significant people enhances the power of the plan and ensures that those who are most important to the person know what’s on it and what role they play in keeping their loved one safe.

The following are components of a safety plan (excerpted from Stanley-Brown Safety Plan):

- Things I should identify as warning signs (how do I feel/what’s happening when I’m feeling unwell);

- How can I soothe myself when I’m feeling unwell (i.e. sewing, beadwork, other art, Sweat Lodge, prayer, Healing/Medicine Lodge, talking circle, etc.);

- Where are places I can go to distract myself or to help myself feel better in the moment (i.e. Powwows, ceremonies, other spiritual/religious gatherings, planting, cultivating or gathering of Traditional medicines, etc.);

- Who are the people on whom I can rely to help me when I’m feeling unwell (i.e. Traditional Healer, other religious/spiritual leader, family member or close relation)

- What are the agencies, hospitals, clinics and/or who are the professionals I can turn to if I’m feeling unwell (i.e. Tribal hospital, Traditional Healer, fellowship support group, behavioral health clinic)

- Identification of the one thing that is most important to me and worth living for: (i.e. family, ceremony or other Traditional ways, career, etc.)

Counseling on Access to Lethal Means

This is a critical part of any safety plan. It gently but directly counsels the person on how to reduce or eliminate access to any potential lethal means. Evidence shows that when there is space and time between a person with suicidal thoughts and the means to act on their thoughts, the more likely the suicidal thoughts will dissipate. Family and other significant people in the life of the Indigenous individual experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors can support this distance by securing firearms or any other weapon, chemicals, or other lethal items (e.g., medicines).

There are unique challenges in Indian Country and rural and frontier areas where hunting and firearms or other weapons are part of the culture. Lawton Indian Hospital in Lawton, OK states that they are very intentional about not taking away the individual’s self-determination. She reported that they always ensure that the individual knows that the choices are their own. She described that they focus on putting the responsibility on the individual to create distance between themselves and the lethal means until they are feeling better.

An Oklahoma gun shop owner has offered that people who are experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors could bring their firearms there for safe-keeping until the crisis had passed. This is an innovative and sensitive suggestion that could easily be implemented by gun shops anywhere.1

For Indigenous people, the most common method used to end their lives was suffocation (hanging).2 When staff provide counseling on access to lethal means with Indigenous people, they should develop a comfort level with addressing all types of methods that may be used. Counseling on access to lethal means cannot be generic and must be meaningful to the reality of the individual and their choices. Conversations with individuals around lethal means may be found in the free, on-line training, Counseling on Access to Lethal Means.

ENGAGE: Key considerations for Indian Country

- Ensure that the health/behavioral health care system creates a clinical pathway of care for those with moderate to high risk of suicide and that staff are trained on all related policies and procedures.

- Assisting people create a safety plan that is resonant with their way of healing.

- Fearlessly counsel on the reduction of access to lethal means with the knowledge that there are many ways in which people think about ending their life.

- People in need of care should be seen within 24 hours and to no more than 48 hours. If people cannot be seen immediately for care, ensure that the system stays in close contact with them until that care connection is made.

- Safety planning is a very effective, person-driven intervention that requires no specialized training except for knowledge of any available community services that supports recovery from suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

- 1E, Bull. (2019, July 8). Personal interview.

- 2Bender, E. (2015, October 7). CDC Report Details Suicide Rate in Native Americans. Retrieved from https://www.medpagetoday.com/psychiatry/depression/53941

TREAT Defined

Treat suicidal thoughts and behaviors using evidence-based treatments.

In a Zero Suicide approach, people experiencing suicide risk, regardless of setting, receive evidence-based treatment to address suicidal thoughts and behaviors directly, in addition to treatment for other mental health issues. Individuals experiencing suicide risk are treated in the least restrictive setting possible.

TREAT Indigenized

As discussed previously, there are good, evidence-based treatments that are highly effective in reducing suicide risk. However, none of them have been validated on Indigenous people. This does not mean that they are not useful when used in ways that honor and respect the cultural traditions of the people, families, and communities served. There have been studies, especially related to the use of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), that have shown promise with Indigenous children who have other behavioral health challenges.1 This study highlighted the significant positive outcomes achieved when blending cultural and traditional practices with DBT.

The onus is on the clinician/therapist to ensure that any evidence-based methodology is culturally-resonant and tailored to the community in which the care is offered. This may mean using different words or concepts while maintaining the fidelity to the framework. A discussion on the use of EBPs in Indigenous health and behavioral health care systems is found here: Adapting Evidence-Based Treatments for Use with American Indian and Native Alaskan Children and Youth and a description of why it is important to consider culture when attempting to implement EBPs into a system of care is located here: Toolkit for Modifying Evidence-Based Practices to Increase Cultural Competence.

As with the DBT study cited above and as stated in earlier sections of this toolkit, a combination of a culturally-tailored, evidence-based treatment and traditional healing ways as practiced by the Tribe are often effective interventions for individuals who may be experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors, especially those Tribal individuals who may be more traditional in their ways.

There are many examples of culturally-based interventions that promote suicide-safer care that can be used alongside or in addition to those that are evidence-based. These examples include:

- A toolkit on the sacred canoe journeys of the people of the Northwest: Healing of the Canoe: A Culturally-Based Preventative Intervention to Reduce Substance use Among American Indian Youth

- Youth participation at fish camps in Alaska: Qungasvik: Toolbox

As well as everything from Stomp Dance ceremonies in Cherokee and Haudenosaunee territories to Sun Dance, Sweat, and Healing Lodges across the Plains and into the Eastern Woodlands and much more in between.

When I entered the Medicine Lodge for the first time in 1970, I had tried to end my life multiple times. I had a serious addiction to intravenous heroin and cocaine and I was diagnosed as having PTSD and a bi-polar challenge. I thought I was the only one who went through a terrible childhood as a result of Mother having been put in a brutal residential school for ten years, from the ages of 6 through 16, but sitting around that sacred fire, I heard my story recounted by nearly everyone in the Circle. I began to believe I was not alone…that my story was not unique…that I could begin to heal with the help of our sacred medicines, our Elders, and the Relatives in that Circle. It’s been nearly 50 years and I’m still healing every day…still holding on to that sacred Circle. I know it works, and I’m here to prove it.

— Mi’kmaq First Nation Elder

Some examples of culturally-relevant interventions that can be partnered with those that are evidence-based are located here:

- Honoring Native Life: Creating Conversation Around Suicide Prevention & Response

- Gathering of Native Americans (GONA) Training of Facilitators

- WeRNative: For Native Youth, by Native Youth

- #ThereIsHope—Suicide Prevention and Awareness on the Pine Ridge

- Project Venture: Adventure With an Indigenous Mind

- The Sky Center: Natural Helpers, A Peer-Helping Program

- Suicide Prevention: A Culture-Based Approach in Indian Country

- Hope on the Reservation: Combating Suicide

SAMHSA's TIP 61: Behavioral Health Services for American Indians and Alaska Natives provides behavioral health professionals with practical guidance about Native American history, historical trauma, and critical cultural perspectives in their work with Native American and Alaska Natives.

Esther Tenorio of Pueblo San Felipe talks about the use of evidence-based treatment with Indigenous people and families here: EBPs in Indian Country.

Tele-Health

Tele-health is becoming popular across Indian Country and offers a way for people to receive care in anonymous and much less threatening ways. Family members or other members of the community are likely to work in these systems and tele-health offers a layer of confidentiality to those who may be ashamed of having to seek treatment for suicidal thoughts or behavior. It is also a way for someone who may be at risk and a long way from services to receive care. An article on tele-medicine in Indian Country can be found here: Avera: Offering Mental Health Care to Reservations through Telemedicine.

TREAT: Key considerations for Indian Country

- Keep in mind that, as with screens and assessments for suicide risk, there is no evidence-based treatment modality for suicide-specific care that has been validated on Indigenous people.

- For some of those Tribes that have maintained their Ancestral ways, the use of Traditional Healers and medicines continues to be highly effective.

- For many of the Tribes, even those who are more traditional in their ways, a combination of traditional and western medicine is often highly effective.

- Western ways will be much more readily accepted by the person seeking services if they know that their traditional ways are honored as well. At Tsehootsooi Medical Center, Traditional Healers are a specialty clinic housed under Medicine.

- Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) with all other providers, including Traditional Healers, to which someone who is at risk for suicide may be referred for follow-up care are extremely critical to suicide-safer care and to the comprehensive implementation of Zero Suicide within a health care system in Indigenous communities. This is especially important in systems that are more remote or frontier, and those that are not full-service and need to refer for inpatient treatment, for example.

- It is critical for Tribally-owned health/behavioral health care systems that are not full-service to develop strong partnerships with the nearest IHS Service Unit. The Service Unit should have representation on the implementation/leadership team and lines of communication with the Service Unit should be nurtured and supported.

- If tele-health is available, encourage the person/family to use this, especially if distance to services or transportation are challenging. Additionally, this intervention is especially effective with those for whom asking for help is challenging or those who fear that their confidentiality is at risk. On the IHS website, there is more information on tele-health in Indigenous health and behavioral health care systems located here: IHS Tele-Education.

- 1Beckstead, D. J., Lambert, M. J., DuBose, A. p, & Linehan, M. (2015, July 26). Dialectical behavior therapy with American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents diagnosed with substance use disorders: Combining an evidence based treatment with cultural, traditional, and spiritual beliefs. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306460315002749

TRANSITION Defined

Transition individuals through care with warm hand-offs and supportive contacts.

In a Zero Suicide approach, organizational policies provide guidance for successful care transitions between levels and types of care. These policies specify how, when, and what contacts and supports are needed to provide uninterrupted care for individuals at risk of suicide.

TRANSITION Indigenized

Staffing is a challenge in many Indigenous health systems. Many locations are remote and staff recruitment and retention is challenging. One potential solution is building community connections to support the health system efforts. Some Indigenous health and behavioral health care systems have developed relationships with Traditional Healers to provide suicide-specific home or community-based care for individuals and families using traditional medicines and interventions. It is critical for Tribal-owned health/behavioral health care organization to develop strong partnerships with the IHS Service Unit in their area. Soliciting IHS representation on the implementation/leadership team and nurturing lines of communication with the Service Unit is strongly encouraged.

Some organizations in Indian Country have addressed the lack of access for people who have screened positive for suicide risk with mobile health vans that visit school systems and communities on Tribal land. Some have developed relationships with public health nurses, community health workers or peer recovery specialists who make home visits to do wellness checks on those who may be at risk but unable to travel long distances to make their appointments.

The element of TRANSITION is critical when implementing effective suicide-safer care in any system but none more so than for those living in areas where there is no public transportation and the nearest health/behavioral health care service is many miles from home. Warm hand-offs to another level of care or follow-up with those who may have screened as being at risk may be challenging.

Crisis Lines and Related Supports

Organizations such as Heartline in Oklahoma and Washington State's Native and Strong Lifeline provide an important link for those who can't easily access care. They can provide follow-up care for those who have been discharged from EDs, inpatient, or if they are between providers. For example, the Integrated Service Division of the Chickasaw Nation Departments of Health and Family Services contracts with Heartline to follow-up with individuals who are discharged to their communities.There is a fee for these services, but for remote and understaffed systems the service can be invaluable. Services to and support for individuals who call the Heartline directly are provided at no cost to the caller.

Non-demand caring contact letters and cards

A non-demand caring contact call/card/note is defined as a contact with an individual who has transferred out of care. It is a brief expression of hope and support of the individual without placing any addition burden or request on them. These calls, cards and letters have been shown to have a positive impact for individuals who have been assessed as at-risk for suicide.

Examples of non-demand caring contact letters and cards for Indigenous people may be found here:

Now Matters Now is a website that offers ways to stay connected with those who have accessed services. It also supports individuals through the use of on-demand, culturally-relevant, digital stories with survivors who offer suggestions for health and wellness.

TRANSITION: Key considerations for Indian Country

- Use mobile crisis teams, peer specialists, Traditional Healers, and public health nurses for those who have reduced access to services because of distance or lack of transportation.

- Ensure that the individual gets from one level of care to the next as expeditiously as possible with no gaps in care. If there will be a gap as a result of distance or transportation, ensure that connection with the individual is maintained. (see point above)

- Create MOUs and ensure partnerships with physical and behavioral health providers within the Tribal community and, if necessary, outside of it.

- Build relationships with the Traditional Healers in the community and ensure that they are represented on leadership/implementation teams.

- Create postcards with symbols, images, and words that convey hope, balance and life. If needed, ask for assistance translating messages into the language(s) of the Tribe(s) served by the health/behavioral health care system. No return address is necessary and no demands on the individual or family are part of this message.

- Have the team who cared for the individual send letters with uplifting messages (i.e., how great it was to meet the person, how much they enjoyed working with them, how they wish them health and wellness, etc.).

- Connect with state or local telephonic supports, such as Heartline in Oklahoma or Native and Strong Lifeline in Washington as a referral source for an individual and/or family.

IMPROVE Defined

Improve policies and procedures through continuous quality improvement.

In a Zero Suicide approach, a data-driven quality improvement approach involves assessing two main categories: fidelity to the essential systems, policy, and care components of the Zero Suicide framework and; care outcomes that should come about when the organization implements those essential components. Continuous quality improvement can only be effectively implemented in a safety-oriented, "just" culture free of blame for individual clinicians when someone with whom they are working attempts to end their life or dies by suicide.

IMPROVE Indigenized

The basic premise of the Zero Suicide approach is that, if fidelity to the framework is part of the culture of the organization, the way care is delivered, outcomes will improve. To simplify the concept of fidelity, let’s look at it like this:

When we get ready to plant some crops to feed our family, there are steps we need to take in order for those crops to thrive and sustain us through the next growing season. If we skip a step or two, it is likely that our efforts to grow our food will fail. We need to ensure that the soil is prepared properly, that there is a good balance between sun and water, and that we have healthy seed to plant. We will ensure that we are attentive to the young seedlings, protecting them from things that may compromise their growth and then, once they are fruitful, we will harvest.

For a health/behavioral health care system, the implementation of Zero Suicide is much like this. There are seven steps that ensure a good harvest (outcome) and, if we skip a step or two, all of our work in trying to implement the other steps may not provide us with the outcomes we expect. This is called fidelity to a framework; following specified steps to prepare the ground, to plant the seed and to protect the crops along the way. So fidelity to the Zero Suicide framework when we are implementing in our health/behavioral health care systems means that each and every element is connected to the other, making not a line, but a circle. All portions of that circle are sacred and attention and honor is paid to each of the elements that make it up.

However, it is difficult to determine what is working and what needs to change if there is no record of what types of interventions are being implemented. Therefore, even if data is collected by paper and pencil, it is critical that it be recorded, maintained and shared.

The Zero Suicide Data Elements Worksheet is a helpful tool when deciding what types of data to collect in order to evaluate: 1) fidelity to the Zero Suicide framework and; 2) how this fidelity is impacting your health/behavioral health care system. To begin, the scope of the impact of loss by suicide is critical to know. If you do not have this information, it is not possible to know whether or not the implementation of Zero Suicide is helping to reduce the loss of life by suicide in the system. As mentioned previously, some Tribes have prohibited, through Tribal Resolution, the release of certain data, deaths by suicide being one of these, so obtaining this data may be challenging. A toolkit with some suggestions on surveillance in Indian Country is located here: SPRC Suicide Surveillance Strategies for American Indian and Alaska Native Communities.

In some Tribal systems, deaths by suicide are recorded as traffic accidents, accidental overdoses or other types of accidents…even though there is evidence to suggest that these deaths were a direct result of self-harm. This false recording is often a result of the surviving family’s request to keep this part of the loss away from the records because of shame. Many Tribes (but certainly not all) across Indian Country believe that, if a person ends their own life, their spirit does not automatically “walk” to Creator, but that it stays in a land apart from Creator. Sacred ceremonies conducted by Traditional Healers amongst some of the Tribes seek to retrieve those spirits and take them to Creator.

Our Tribe believes in “ghost sickness.” We do not talk about anyone who has ended their own life. We believe that if we do, it will bring that energy to us and will cause others to do the same (take their life). So we don’t talk about it at all.

— Cultural Liaison working with one of the Southwestern Tribes on Zero Suicide1

My job in Sundance is to go out into the Spirit World to a place where the spirits of those who ended their own lives reside. Because they took their own lives, they are blinded to where they need to go in order to enter the sacred space where Creator resides. Through sacred ceremonies, special prayers and through the use of our traditional medicines, we can help those spirits find their way to Creator by acting as their eyes, their guides. Once they are on this road, Creator welcomes them home.

— Anishinabek Buffalo Dancer2

Continued frank and open dialogue, informed by the cultural ways of the Tribe, with the Tribal leadership, Elders, Traditional Healers, youth, and the rest of the community regarding loss by suicide will act to “take the sting” out of this topic. However, as stated throughout this document, extreme care needs to be taken to understand how the Tribe articulates death and dying, especially loss of life by suicide, so cues should always be taken from the Elders of the community as well as from the Tribal leadership. This can mean the difference between the Tribe’s acceptance of suicide-safer care and the rejection of it.

It is helpful to choose three or four points on the Data Elements worksheet so that you can get a feel for how best to collect the data and how to synthesize it into reports that show forward movement in the creation of safer suicide care. An explanation of some data collected and used for quality improvement in Indian Country may be found here: Outcome Story: Chickasaw Nation Departments of Health and Family Services.

Beginning modestly will aid in the development of confidence around data collection. Positive outcome data (i.e. numbers of people who were seen in the ED during the month of July vs numbers of people who were screened for suicide risk) will be useful when applying for grants or when communicating the importance of a comprehensive plan for making death by suicide a “never event” in their community to Tribal leadership. While the information about numbers of Tribal members lost to suicide may be important to Tribal leadership, the numbers of lives saved through the implementation of the Zero Suicide framework within the health/behavioral health care system serving them would also be very important for them to know.

IHS, in working with their Zero Suicide Initiative grantees, recommends the following data points, among others, to be collected by their grantee systems:

- Numbers of screenings performed (universal screening with a goal of 100% for every person who comes for services regardless of reason why)

- Numbers of those above screening cut-off who receive a full suicide risk assessment (with a goal of 100%)

- Numbers of those receiving a full risk assessment who have a collaboratively-developed safety plan (with a goal of 100%)

- Numbers of those with a collaboratively-developed safety plan who have been counseled on reduction of access to lethal means (100% goal)

- 100% of all behavioral health clinicians use evidence-based practices to directly treat those at risk for suicide

- 100% follow-up on those who may be at risk for suicide to ensure safe transitions through care

- 100% documentation of every loss by suicide

Most health/behavioral healthcare systems in Indian Country have departments that are dedicated to the coding and billing using data analytics based on service codes. Utilize these experts to create reports that can be helpful to the system when working to improve services.

Data Resource

IMPROVE: Key Considerations for Indian Country

A note about research in Indian Country

Histories of forced relocation and multiple attempts at genocide, some of which are still occurring today, make trusting research and the people who do it difficult for many Native communities. Historically, some research has been used against Tribes and Tribal communities and, as a result, many of them have laws prohibiting the dissemination of their statistics.

As stated previously, keep in mind that federally-recognized Tribes are Sovereign Nations and have the right to self-determination, including what data they will share and what they will not.

Many Tribes and Tribal people believe that respectful research never evaluates sacred cultural traditions and believe that the examination of those traditions by others is disrespectful and dishonoring. Up until the late 1970s, it was illegal and punishable by fines or imprisonment to practice traditional healing ways, religions or spirituality, as well as to use Traditional Healers and medicines. The memories remain of those centuries when Native ways were outlawed and many ceremonies continue to be inaccessible to others not of the Tribe or community. That should be respected and honored.

Academic institutions such as the Center for American Indian Health at Johns Hopkins University, working with staff enrolled in Tribes throughout the nation, have been able to partner with Indigenous communities in respectful, honoring ways to improve their health and well-being. Suicide-safer communities and the development of healing ways that support and promote those ways have been important parts of their work.

“If the research you are proposing to do doesn’t benefit the community, then it’s not research worth doing here.”

— Tribal Elder

- Not every Tribe or Tribal site has an electronic health record (EHR). Many are capturing data by paper and pencil. No matter what…capture it! Once it is captured, make certain to share it with staff, with leadership and with the Tribal community in which you are working. Plan out how to make sure that information is shared across providers and clinics so that suicide risk information follows individuals through every door they enter in health system.

- It’s important to know the extent of the challenge of loss by suicide in the community before crafting responses to it. This knowledge will also assist with conveying the urgency of the need to address the challenge to the Chief/Governor/President/Chairperson, the Tribal Council or the community.

- Decide upon four or five data points that would be helpful for the health/behavioral health care system to know in order to ensure that the goals of the system are being met, the most critical of these being the reduction of loss of life to suicide. These data points may include numbers of screenings that are completed, numbers of assessments done for individuals screening positive, numbers of individuals who are placed on a care pathway for safer suicide care, etc.

- Utilize your Clinical Applications Coordinators (CACs) for the creation of pick lists to ensure that services that are being provided are billable and that data can be extracted for reports.

- Regularly share data on positive impact with the leadership/implementation team, especially with the Chief/President/Governor/Chairperson, the Tribal Council, and Traditional Healers, Elders, youth and larger community. Data may be published in Tribal newsletters or presented at community gatherings, in infographics at health fairs, etc.

Conclusion

Suicide Prevention in Indian Country

Suicide looks very different in Indian Country than it does in the general population. Nationally, suicide tends to skew middle-aged and white; but among Indigenous people, 40 percent of those who die by suicide are between the ages of 15 and 24. Among young adults ages 18 to 24, Indigenous people have higher rates of suicide than any other ethnicity, and higher than the general population.1

To indigenize the Zero Suicide framework, attention must be given to the unique values, beliefs, identity, behaviors, and social norms to provide safer suicide care that is resonant with the individual receiving it. Among Tribal Nations, no one group is homogenous in all aspects. We must acknowledge these differences, delivering suicide care in culturally appropriate and thoughtful ways.

Implementation Lessons Learned

Implementing the Zero Suicide Framework in Indian Country

The best teachers are those who have direct experience doing what they teach. Dr. Shannon Dial, Executive Officer of the Integrated Services Division of the Chickasaw Nation Departments of Health and Family Services shares her experience implementing Zero Suicide in Indian Country here.

According to Dr. Shannon Dial, Executive Officer, Integrated Service Division, Chickasaw Nation Departments of Health and Family Services, and implementer of Zero Suicide since September of 2016, there were many lessons they learned throughout their implementation journey and the full story is here:

Outcome Story: Chickasaw Nation Departments of Health and Family Services.

- Embed implementation steps in the electronic health record (EHR) whenever possible.

- Modify current documentation templates to incorporate your new screening and assessment practices.

- Conduct chart reviews periodically to ensure documentation is accurate.

- Personalized follow-up with patients makes a huge difference (i.e. phone call or handwritten caring contact note).

- Nursing plays a huge role in Zero Suicide.

- Start collecting data from the beginning (use the Zero Suicide Data Elements Worksheet as a guide).

- Review data often and share it widely.

- Hire or select Zero Suicide implementation team members intentionally.

- Recruit as many champions as you can.

“The more we have listened to our patients and reviewed relevant research, it is evident that inpatient treatment is not always a viable option to ensure improvement and success. It additionally adds a critical risk window once they discharge that we can avoid through diversion.”

— Tribal Elder

Please explore the additional resources below and, remember, implementation is not an event—it’s a process.

Additional Resources

IHS Suicide Prevention and Care Policy

Prevention Resources

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Native Americans

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center: AI/AN

- To live to see the great day that dawns: Preventing Suicide by American Indian and Alaska Native youth and young adults

- SAMHSA Preventing and Responding to Suicide Clusters in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities

- One Sky Center: The American Indian/Alaska Native National Resource Center for Health, Education and Research

- One Sky Center: A Guide to Suicide Prevention for American Indian and Alaska Native Communities

- NPAIHB Indian Leadership for Indian Health THRIVE

- We Belong: Life Promotion to Address Indigenous Suicide Discussion Paper

- Healing the Body with United Indian Health Service

- Indian Health Service Suicide Prevention and Care Program

- Honoring Native Life: Native American Suicide Prevention Clearinghouse

PSA and videos for Indigenous Youth

- Arlee Warriors

- Join the Warrior Movement: Every Life Matters

- Native American Suicide Prevention PSA

- We Shall Remain

- Native Cry Suicide Prevention PSA

- Children on the Rez - Blue Mountain Tribe

- Seven Generations

- Wingspan Media: You are Irreplaceable

Prevention Resources for Native Youth

- Your Life Your Voice

- Healthy Native Youth Curricula

- Center for Native American Youth

- WeRNative: Wanting to End Your Life

- WeRNative: Get Your Gear

- Advocates for Youth

Hope and healing for Indigenous people

- Full Circle: The Aboriginal Healing Foundation & the unfinished work of hope, healing & reconciliation

- Hope for Life Day Toolkit

This work was funded through a contract with IHS.

- 1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). 1999-2020 Wide ranging online data for epidemiological research (WONDER), multiple cause of death files [Data file]. National Center for Health Statistics. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html