With 34 hospitals and 400 clinics across six states, Intermountain Health is a significant provider of health care throughout the Mountain West. Behavioral health care is a priority for the system: five of Intermountain Health’s hospitals offer inpatient behavioral health care, and three others have Behavioral Health Access Centers, which include emergency care centers and crisis stabilization units. In 2022–2023 alone, the system recorded 788,395 emergency room visits.

Suicide Care Journey Stories

SC CoIIN Objective

In joining the Suicide Care Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (SC CoIIN), Intermountain Health sought to improve its suicide prevention training for staff and its care transitions for discharged clients. It also wanted to examine how refinements to its electronic health record (EHR) system could better support the system’s suicide care pathway. With research suggesting that 83% of people who die by suicide are seen by a health care provider in the year before their death,1 team members were keen on implementing these improvements in primary care, Emergency Department, and crisis center settings—locations where they saw the most people at risk for suicide.

“We’ve been on a suicide safer care journey for many years now,” said Kim Myers, behavioral health clinical program manager at Intermountain Health. “We recognize that we still have a lot of opportunities to learn from other health systems, and that this is a long-term journey [that requires] continuous quality improvement to really update the way we care for people with suicide risk throughout the system.”

“We recognize that we still have a lot of opportunities to learn from other health systems, and that this is a long-term journey [that requires] continuous quality improvement to really update the way we care for people with suicide risk throughout the system.”

Previous Experience with Suicide Care

For nearly a decade, Intermountain Health has had systems and processes in place to address suicide. In 2015, Intermountain Health implemented a Care Process Model for the management of suicide, which provided guidance on how to screen for suicide and what to do if a patient exhibited suicidal ideation.2 In 2018, Intermountain Health created an internal suicide prevention committee. This committee was reorganized in 2022.

Suicide prevention is also integrated into patient care. Primary care health providers use the PHQ-9 screening tool3 as a routine part of their practice, and patients who screen positive for suicide are given a full Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)4 risk assessment. Intermountain Health has also put in place guidelines for referral to behavioral health care and safety planning. Similar processes and protocols exist for patients who are in specialty behavioral health services, who are admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, or who arrive in crisis at an Emergency Department.

Although screening and assessment for suicide were widely adopted, individualization of care was sometimes difficult, especially from a workflow perspective. “You don’t want to give providers the same guidance for somebody who’s showing up with suicide risk for the first time as somebody who lives with suicide risk and who is seeing a practitioner weekly,” said Myers.

Intermountain Health uses a robust data collection system to track trends in patient care. A Suicide Safer Care dashboard displays data on suicide screenings, assessments, and rates of completed safety plans across settings. Intermountain Health has also partnered with the Utah Office of the Medical Examiner to create a dashboard that tracks deaths by suicide across the state. These data help Intermountain Health staff track whether people who died by suicide interacted with the health system before their death.

Before joining the SC CoIIN, Intermountain Health hired behavioral health navigators to follow up with patients at risk of suicide within three days of discharge. The addition of these navigators has smoothed the continuity of care for patients during a high-risk time of transition. System data show that between 58% and 66% of Intermountain Health patients in behavioral health settings are now being seen for a follow-up visit within seven days of discharge. Nationally, only between 27% and 48% of discharged patients are seen at a follow-up visit.5

Interventions Implemented

Intermountain Health implemented a number of changes during their participation in the SC CoIIN, largely in two specific areas of care: acute and primary care.

1. Collaborative safety planning

In acute care, the team focused on improving their collaborative safety planning processes. Collaborative safety planning requires conversations between providers and patients about specific coping skills and plans for what to do in the event of a crisis. However, Myers said that this level of collaboration between provider and patient was not consistently happening before the SC CoIIN.

“We just sort of expected providers to be able to do it, and go through the safety planning form, and know how that translated into good suicide care,” she said. “But a lot of providers hadn’t been trained or felt like it wasn't meaningful to patients—that it was just another checkbox that they were supposed to do.”

To examine the importance of the safety plan, Intermountain Health conducted a survey with 51 patients at risk of suicide who had recently been discharged from care. Thirty-five respondents indicated that they had used the safety plan since leaving the hospital. Forty-five respondents said that they thought they would use it in the future.

“Being able to take that information back to providers to say, ‘this is more than a checkbox; this is meaningful care to the patient’ has been impactful,” said Myers.

As a result of the survey, Intermountain Health has begun training providers at one hospital on the Stanley-Brown Safety Plan,6 an effective collaborative safety planning tool. Myers has also observed more providers across the system buying into the importance of collaborative safety planning.

2. Improving EHR workflow

In primary care, the Intermountain Health team worked on improving their EHR workflow for suicide care. Myers described the existing workflow for primary care specialists as “clunky” and “having some missing elements.” For example, the risk assessment did not highlight recent sleep disturbances, chronic pain, or financial stressors as risk factors—even though hospital system data consistently indicated that these items were associated with suicide. Navigating through the suicide risk assessment in the EHR also necessitated “a lot of clicking” for physicians, licensed therapists, and advanced practice providers, which often served as a barrier to use.

During the SC CoIIN, the Intermountain Health team mapped out their existing EHR workflow and proposed changes to become more in line with best practices. Among the changes are better alerts when a patient indicates a suicide concern and more prominent display of suicide assessment results. This latter change would enable clinicians “to go right to their part of the work, which is really making that clinical decision around whether a patient is at high suicide risk,” said Myers. As Intermountain Health is switching EHR system providers, these changes will be adopted when the new EHR goes live.

Key Successes

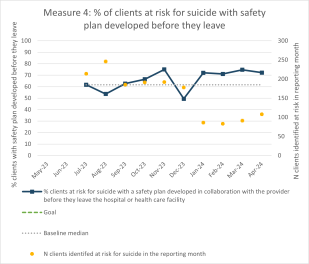

One of Intermountain Health’s key goals was to improve the use of safety planning in their suicide care pathways. So, they established a goal: they would aim to have 60% of patients at risk for suicide complete a safety plan before discharge. In the 10 months between July 2023 and April 2024, Intermountain Health reported meeting or exceeding that goal eight times, while only falling short of it twice.

The mapping out of a suicide care pathway within a new EHR system was another key success. Myers said that other SC CoIIN participants were instrumental in this process, as they provided valuable advice and perspectives about how to use EHRs to support a suicide care pathway. The Intermountain Health team “took lessons from what was working with other SC CoIIN participants’ EHR workflows” as they charted a new way forward.

Finally, because of this work, Intermountain Health has also redoubled their staff training efforts. They have implemented both live and computer-based training for clinicians on how to conduct collaborative safety planning. They are also developing suicide-specific care trainings for their medical assistant residency program, and are planning to offer annual, systemwide trainings on suicide prevention to all staff, including clinicians, nurses, food service workers, and orderlies.

“Training is foundational for suicide prevention,” said Myers.

Lessons Learned

- EHR workflow is an important, but often overlooked, item in the suicide care pathway.

- Coordinating improvements in a large healthcare system is difficult because many different people are responsible for different parts of the suicide care pathway.

- Sharing data with practitioners, clinicians, and hospital staff helped provide a context for conversations about successes and opportunities for suicide care.

- Other organizations implementing Zero Suicide offered a wealth of knowledge about establishing a suicide care pathway.

Future Opportunities

Intermountain Health plans to continue their suicide safer work after the conclusion of the SC CoIIN. They are creating a new onboarding and training plan for crisis workers that will emphasize the system’s suicide prevention priorities and protocols. They are also updating their suicide safer care data dashboard to emphasize prevention and are in the process of refining their suicide care workflows as they migrate to a new EHR system.

- 1

Ahmedani, B. K., Simon, G. E., Stewart, C., Beck, A., Waitzfelder, B. E., Rossom, R., Lynch, F., Owen-Smith, A., Hunkeler, E. M., Whiteside, U., Operskalski, B. H., Coffey, M. J., & Solberg, L. I. (2014). Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(6), 870–877. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3

- 2

Intermountain Healthcare (2020, December). Care process model: Diagnosis and management of depression. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://intermountainhealthcare.org/ckr-ext/Dcmnt?ncid=51061767

- 3

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (1999). Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06165-000

- 4

Posner, K. (2007). Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t52667-000

- 5

National Committee for Quality Assurance. (n.d.) Follow-Up After Hospitalization for Mental Illness (FUH). https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/follow-up-after-hospitalization-for-mental-illness/

- 6

Stanley, B., & Brown, G. K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.01.001